The Anti-Populist Elite Political Establishment Are Fast Giving Up On Democracy

Once they start talking about banning political parties - Beware!!

Last week, we discussed the corrupt usage of the term ‘far-right’. This week, we explore how elite hysteria about the threat posed by putative far-right parties has led to a growing willingness to countenance the use of authoritarian repressive measures to stem their influence.

‘This time, the far-right threat is real’ is the title of a commentary in Politico. The threat it refers to is that the ‘right-wing surge in the polls seems bigger and bolder, with one predicting the nationalist right and far-right could pick up nearly a quarter of seats in the European Parliament in June.’ People are clearly voting the wrong way in Europe, and as far as some commentators and politicians are concerned, democracy is not working as it should.

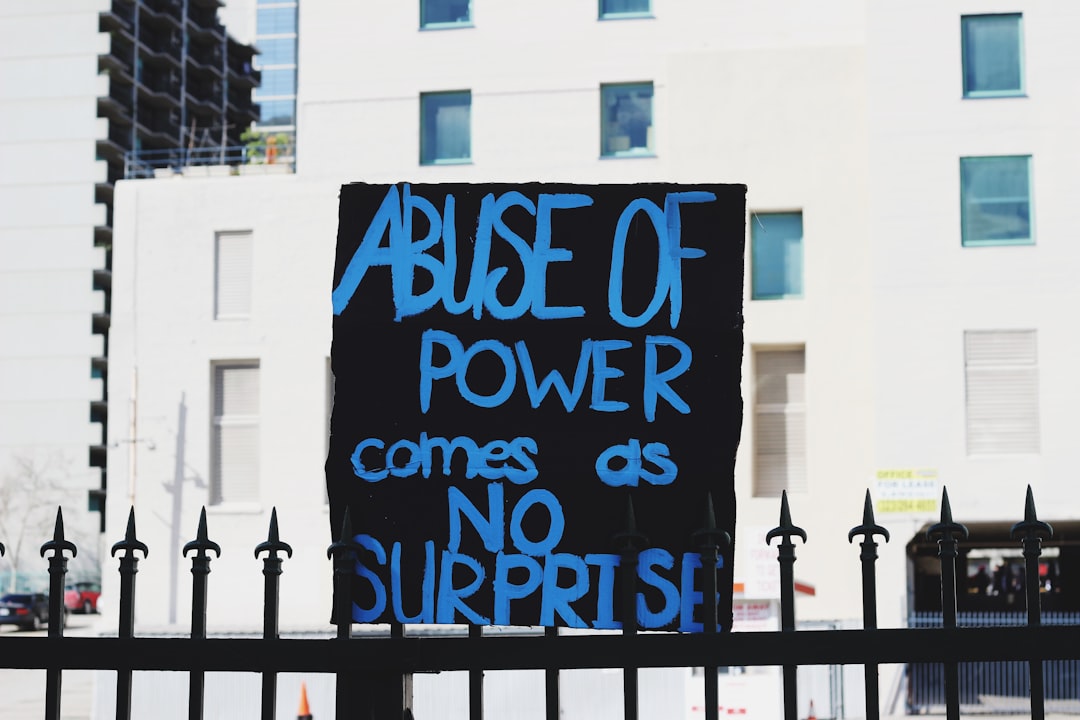

From the standpoint of the anti-populist establishment, parties that challenge its hegemony must be discredited and de-legitimated. One way that this goal is pursued is through branding such parties as far-right or fascist or a threat to democracy. If indeed the ‘right-wing surge in the polls’ can be represented as a threat to democracy, it follows that authoritarian repressive methods can be called upon to fix the problem. Those who believe that the threat posed by populist movements needs to be managed through the application of special measures often take the view that their form of repression is not really repression since it is motivated by sincere and benevolent motives. From this standpoint, anti-democratic methods to save democracy appears to be a sensible course of action rather than a contradiction in terms.

Poland has become a laboratory for an anti-democratic experiment. Authoritarian anti-democratic action is justified by the new Polish Government of Donald Tusk on the grounds that it is necessary to save democracy. Tusk is determined to root out all traces of influence of the previous Government. To that end, he has brought the state media under his political control and ousted his opponents from Poland’s Constitutional Court. A man who formerly swore on the rule of law Bible has decided that emulating the behaviour of a banana republic dictator is a small price to pay for saving democracy in Poland. Not even the arts are immune from the heavy-handed behaviour of the Tusk regime. The newly appointed Minister of Culture and National Heritage, Bartlomiej Sienkiewicz, decided to prevent Polish artist Ignacy Czwartos from exhibiting at the Polish Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. No doubt, this heavy-handed decision was motivated by the need to defend democratic art from the threat posed by far-right artists. Tusk’s defence of democracy is indifferent to the valuing of artistic freedom.

It is in Germany that democracy faces its gravest threat. The hysterical reaction of the mainstream media and the political establishment to the steady rise of the Alternative for Germany Party (AfD) in the polls has acquired pathological proportions. For many months, a growing number of politicians and members of the cultural elite have concluded that since anti-democratic ideals inspire the AfD, the best way of dealing with it is by banning this party. Last year, Frank-Walter Steinmeier, the Social Democratic President of Germany, asserted, ‘it is our hands to put those who despise democracy back in their place’. The implication of his statement was all too clear. As far as he is concerned, the AfD is a legitimate target of state repression. Arguing in the same vein, an editorial in German news magazine Der Spiegel last year called for the ‘enemies of the constitution’ to be banned, claiming that ‘it’s time to defend democracy with sharper weapons’.

Since the turn of this year, the demand to ban the AfD has become increasingly common. This reaction is unsurprising since the AfD has been polling better than all the three governing parties. Despite constant attempts to place this right-wing party under a political quarantine, a growing section of the electorate supports it. In recent weeks, mass anti-AfD demonstrations were held throughout Germany. These rallies, actively supported by the political establishment and the media, aim to isolate the party from its electoral support. The pretext for holding these rallies was the revelation that senior AfD aides attended a ‘secret’ meeting with ‘new right’ figures, including Martin Sellner, the leader of Austria’s Identitarian Movement. According to journalists associated with the Correctiv magazine, those in attendance discussed the prospect of mass deportations, including of German citizens from migrant backgrounds. It made no difference that the AfD leadership publicly distanced itself from these proposals and sacked the aides in attendance. The media and the political establishment treated this event as if it were a meeting designed to launch the Fourth Reich.

The mass rallies failed to seriously erode the AfD’s electoral support, which is why there is now a constant stream of articles devoted to the question of ‘what next’?

The premise of the ‘what next’ question is that since the AfD threatens democracy, some extraordinary repressive action may be necessary. Typically, deliberation on the ‘what next’ question takes the form of drawing up a balance sheet of the pros and cons of banning this party. A discussion titled, ‘How should Germany deal with its far-right problem – and could it ban the AfD?’ published in The Guardian is paradigmatic of the conduct of ‘what next’ deliberation. None of the 6 participants in this debate demonstrated a principled opposition to banning the AfD. Some of them are reluctant to go down the banning route on the grounds that it would not achieve the desired outcome and, indeed, might prove counterproductive.

At the same time, none of the participants appear to rule out banning a political party supported by at least 1 out of 5 German voters on principle. Andreas Busch, a professor of political science at the University of Göttingen, stated that the German Constitution’s provision to ban extremist parties ‘is a sharp sword, and so it must be used with great caution’. Nevertheless, he adds that ‘to rule out an application now is to ignore an option that the basic law provides with good reason’. Another academic, Holger Hestermeyer, an international and EU law professor at the Vienna School of International Studies, echoes the wait-and-see approach. ‘A ban offers no salve to the rise of extremism’, he stated before adding, ‘but if it is both legally possible and politically useful, it is time to consider one’.

The experience of history indicates that once banning a political party is regarded as ‘legally possible’, it is only a matter of time before it will be represented as politically necessary. Although the focus of anxiety of the anti-populist German elites is the AfD, its real concern is with the unreliability of the electorate. This is another way of saying that they don’t trust how democracy works.

Defensive Democracy

Since the 1930s, the fear of the electorate's behaviour has encouraged sections of the German political establishment and their intellectual supporters to support what they call ‘defensive democracy’. Supporters of defensive democracy assert that to prevent the recurrence of anti-democrats winning power through the ballot box; the state must have the power to ban extremist parties. This assertion is justified by the spurious assertion that the Nazis were able to seize power by ‘exploiting’ the democratic system. Yet it was precisely because they could not come to power democratically that the Nazis came to power through a coup d’êtat.

The concept of defensive or militant democracy was originally developed during the 1930s by the German political scientist Karl Lowenstein in response to the threat posed by extremist authoritarian movements. Militant democracy is a form of governance that self-consciously uses undemocratic instruments to protect a liberal-democratic constitution from the threat posed by the emotionalism of the popular mind. Lowenstein made a clear distinction between emotional and rational forms of governance. He asserted that a rational form of governance relied on insulating state institutions from the ‘verdict of the people’. He wrote:

‘A pertinent illustration chosen from the experience of a democracy may clarify the vital difference between constitutional and emotional methods of government. The solution of the recent political crisis in England by the cabinet and the Commons was sought through rational means. To have left the issue to the verdict of the people would have been resorting to emotional methods, although general elections are manifestly a perfectly legitimate device of constitutional government’.1

Lowenstein believed that fascist techniques of manipulation could easily manipulate democratic institutions. Lowenstein feared that since liberalism could not match the emotional appeal of fascism, the ‘verdict of the people’ posed a danger to the prevailing political order. He was therefore critical of what he characterised as ‘democratic fundamentalism and concluded that important issues should not be left to the ‘verdict of the people’. He warned that;

‘They [the fascists FF] exploit the tolerant confidence of democratic ideology that, in the long run, truth is stronger than falsehood, that the spirit asserts itself against force. Democracy was unable to forbid the enemies of its very existence the use of democratic instrumentalities. Until very recently, democratic fundamentalism and legalistic blindness were unwilling to realize that the mechanism of democracy is the Trojan horse by which the enemy enters the city.’2

The evoking of the image of a Trojan Horse to underline the perils of an unregulated democratic public sphere spoke to a profound sense of unease towards the masses. It also highlighted a lack of confidence in the ability of a democratically minded constituency to uphold and defend the truth against falsehood.

Loewenstein did not shy away from explicitly endorsing an illiberal defence of liberal democracy. His was a social engineering approach that regarded the psychology of the popular mind as the terrain on which fascism flourished. ‘In order definitely to overcome the danger of Europe's going wholly fascist, it would be necessary to remove the causes, that is, to change the mental structure of this age of the masses and of rationalized emotion’, he wrote.3 To achieve this objective, Loewenstein was prepared to opt for what he called ‘authoritarian democracy’. He concluded that;

‘Perhaps the time has come when it is no longer wise to close one's eyes to the fact that liberal democracy, suitable, in the last analysis, only for the political aristocrats among the nations, is beginning to lose the day to the awakened masses. Salvation of the absolute values of democracy is not to be expected from abdication in favor of emotionalism, utilized for wanton or selfish purposes by self-appointed leaders, but by deliberate transformation of obsolete forms and rigid concepts into the new instrumentalities of “disciplined” or even – let us not shy from the word – “authoritarian,” democracy’.4

Loewenstein’s embrace of authoritarian democracy highlights the ease with which periodically liberal elitism adopts illiberal solutions to neutralise its opponents. If, indeed, liberal democracy is only suitable for the ‘political aristocrats among the nations’, then it is likely to become a problem and not the solution to the challenges posed by modern life. That was why, for him, there was no contradiction between seeking to preserve democracy using undemocratic methods.5

Loewenstein’s distrust of popular sovereignty and his preference for an aristocratic form of authoritarian democracy was widely shared by policymakers charged with the political reconstruction of Western Europe in the post-World War Two era. The current version of militant democracy emerged in response to populism, not fascism. Nevertheless, it, too, wants to protect democracy by using essentially undemocratic means. Currently, this approach is advocated by a teaching kit directed at young people and recently published by the Council of Europe. Pointing to the challenge presented by nationalist parties, it warns that ‘it may be necessary to limit the right to freedom of expression of certain groups, despite the importance of this right to the democratic process’.6

The casual manner with which the Council of Europe signals its willingness to limit free speech indicates that, as far as it is concerned, democracy has become a negotiable commodity. That is why it is important not to interpret the campaign to repress the AfD as a causa sui generis. The current panic about democracy is hospitable to the encroachment on freedom by authoritarian-minded oligarchs. Populist parties and protestors – rural and urban – need to beware and ensure that they will not allow themselves to be placed under quarantine or banned out of existence.

Loewenstein, Karl.1937. “Militant Democracy and Fundamental Rights',“ American Political Science Review 31(3): p. 417

Loewenstein 1937 p.428.

Loewenstein, Karl. 1937b. “Militant Democracy and Fundamental Rights II.” American Political Science Review 31(4)) p.652.

Loewenstein, Karl. 1937b. “Militant Democracy and Fundamental Rights II.” American Political Science Review 31(4) p.657.

Maddox, G. (2019, ‘Karl Loewenstein, Max Lerner, and militant democracy: an appeal to “strong democracy”’. Australian Journal of Political Science, 54(4).

Council of Europe, ‘Compass: manual for Human Rights; education with Young people’, https://www.coe.int/en/web/compass/democracy

Maybe I'll explore the question of the dangers represented by the banning impulse

You are right their big problem is their lack of legitimacy - which they cannot solve anytime soon