The Miracle Of Freedom’s Rare Appearance

My wife returned from our local second-hand bookshop with a little book titled In Praise of Freedom. It was published in 1949 – 4 years after the end of World War 2 and the totalitarian darkness that cast its shadow over the 1930s and 1940s, which must have motivated the publication of this book.

This short publication aimed to acquaint readers with what a carefully selected group of freedom-loving historical figures said about liberty. It is a lovely anthology of excerpts praising liberty. It is full of inspiring poems, short statements, and quotes, such as this couplet from Milton:

‘his is true liberty, when freeborn men,

Having to advise the public, may speak free’.

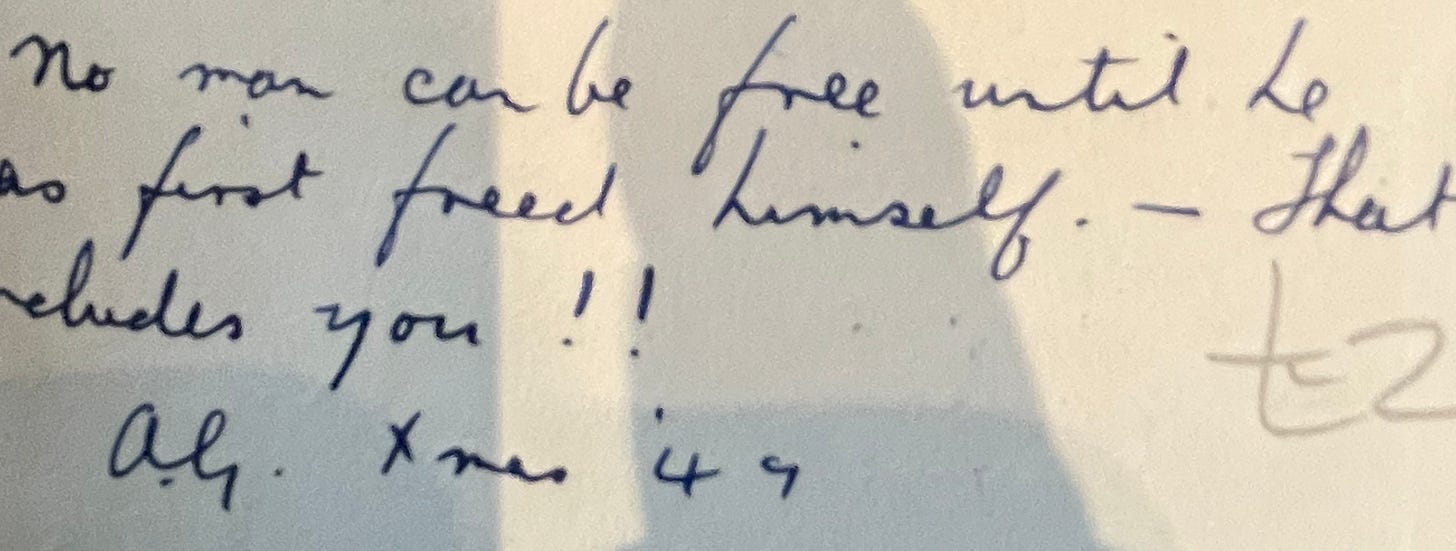

I really enjoyed reading the reflections of figures like Pericles, Tacitus, Spinoza, and T.S. Eliot. However, what caught my attention were not the quotes from these authoritative historical figures offering their views on liberty, but the inscription handwritten in ink on the front page. It states,

‘No man can be free until he has first freed himself – that includes you!!!’

It is signed A. G. Xmas 49.

When I read the words ‘that includes you’, I could not help but feel that this was also a pointed remark directed at myself.

As always, the ideal of living freely excites my imagination. As a young child, I lived through the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, when – until it was crushed – the spirit of freedom reigned supreme. As the Soviet tanks rolled into Budapest to occupy its streets, my father knew that, at least for now, we would lose our freedom to a powerful superpower. Nevertheless, he assured me that ‘our turn would come’. Since that moment, I learned that though our turn did come, the preservation of freedom requires constant vigilance.

In her essay ‘What is Freedom’, published in 1960, the political philosopher Hannah Arendt wrote of the ‘miracle of freedom’s rare appearance’[ii]. Arendt’s reference to freedom as a miracle that rarely appears serves as a warning that we should not take our liberty for granted. In 1960, the principal threat to freedom appeared to be the totalitarian impulses unleashed during the interwar era in Germany and the Soviet Union. In the 21st century, freedom is far more banal. Powerful forces from within western culture continually challenge it. Though the attacks on freedom are rarely explicit, it is frequently dismissed as not a big deal. In the current era, the value of freedom is trumped by other concerns. For example, in the Anglo-American world, the right to free speech is frequently restricted on the ground of protecting people from offence.

The widespread acceptance of the astonishing loss of freedom during the Covid pandemic lockdown highlights a reality where in the name of public health, Governments had no problem forcing people to give up their freedoms. Evidently, the advice regarding the need to ‘free yourself’ did not seem relevant for people who were ready to exchange their status as free citizens for that of potential patients.

The cultural devaluation of freedom in the contemporary world is most strikingly expressed in the way that the term liberty has become emptied of meaning. Frequently liberty is even dismissed as an archaic term used by simple people who are nostalgic for a bygone past. Alternatively, liberty is caricatured as a rhetorical device associated with the ideology of the far right. ‘Michigan coronavirus protesters shout "liberty!" — as right-wing anti-lockdown rhetoric weaponizes freedom’, argues one commentator. An article in The New York Times, titled, ‘How Conservatives Weaponized The First Amendment’, conveys a similar message[.

That the First Amendment – which protects free speech – is portrayed as weaponised and, therefore, can be a threat frequently suggests that, at least for some, freedom itself has acquired dangerous and negative connotations. Indeed, some go so far as to declare that Free Speech is Hate Speech. According to one account, Hate Speech is ‘The Dark Twin of Free Speech’. Often, the supposed unregulated freedom of expression is diagnosed as a threat to society. ‘Want Unfettered Speech? Get Far-Right Attacks Like The Buffalo Shooting’ warns a commentator in The Independent[. From this perspective, the real threat is too much free speech rather than too little. The censor emerges as a force for good protecting society from a world where people feel free to say what is on their minds.

When, as today, freedom so often comes with an alarmist health warning – you know that society is in big trouble.

Instead of celebrating freedom as the medium through which the human spirit can express itself and develop its capacities, it is frequently regarded as a potential threat. All too often, freedom is accused of representing a menace to individuals, groups, or society. Take the example of the beheading of the French teacher, Samuel Paty, by an Islamist murderer, who objected to this educator showing pictures of the Prophet Muhammad in his classroom. Sadly, far too many commentators appeared more interested in questioning the freedom of this teacher to express his view on these pictures than in condemning the barbaric act of his beheading. Roshan M Salih, Editor of the British Muslim news site 5Pillar, tweeted:

‘Charlie Hebdo must be shut down immediately by French authorities. This racist, islamophobic rag is causing community relations to completely break down with its repeated provocations. They are literally crying fire in a crowded theatre. Freedom of speech isn’t worth civil war’.

Actually, protecting freedom is worth a civil war! If we lose our voice and fear speaking freely, all our freedoms are put to question. Free speech is the foundation for all democratic freedoms. Once we fall silent, democracy disintegrates. So yes, it is worth going to war to preserve our freedom to express ourselves.

We would not possess many of our liberties if, in the past, the cause of freedom did not motivate people to fight a civil war to achieve it. Writing in the middle of the English Civil War, the poet John Milton reminded his readers that when God gave Adam reason, ‘he gave him freedom to choose, for reason is but choosing’. His insistence that freedom is humanity’s birth right has inspired generations of freedom lovers. His insistence that ‘reason is but choosing’ provided a powerful argument for the freedom of the press and offered a moral case for uncensored reading.

Unfortunately, in the contemporary world, it is the views of Salih rather than of Milton that are likely to influence the outlook of western cultural and educational institutions. Of course, very few cultural influencers go as far as Salih and implicitly blame the beheading of Samuel Patty on his exercise of freedom of speech. But in one form or another, many of them express the sentiment that the exercise of freedom is such a risky business that in many instances, it needs to be curbed in the interest of society and its members. Salih demands that free speech should be traded away in exchange for preventing a civil war. Others argue that freedom should be traded off for the sake of public health, security, and happiness or for the sake of preventing offence.

What I characterise as the Freedom-Security trade-off is based on the premise that the right to liberty must be balanced against a variety of other concerns. Some supporters of this trade-off claim that the freedom to pursue individual goals may well create or intensify inequalities. Consequently, they suggest that freedom needs to be reconciled with equality. In public life, there is a widespread affirmation for the presumption that equality is a first-order concept to which freedom must defer. A similar sentiment is conveyed in relation to the war on global terrorism, and governments openly argue that curbs on freedom are the price we need to pay for national security.

Calls for one version or another of the freedom-security trade-offs are not simply confined to emergency situations, such as the coronavirus pandemic. The Freedom-Security trade-off dominates virtually every dimension of social experience. Arguments for censoring speech often assert that such limits are necessary for ensuring that people are not hurt or offended. From this standpoint, censorship is justified as a form of public therapy that protects people from feeling hurt. In this case, freedom is traded against the need for respect and self-esteem. The freedom to pursue scientific experiments and to innovate is often restrained by the imperative of safety and concern with side effects. The trade-off of freedom for safety also impacts contemporary childhood. The loss of independent mobility and freedom of the outdoors for children symbolises the intimate coupling of an illiberal imagination and fear. In universities, academic freedom is frequently undermined by the rulings of ethics committees that claim that liberty must give way to ‘ethical’ considerations.

The securitisation of freedom

Thomas Hobbes is the philosopher most widely associated with assigning safety a central role in political discourse. In the aftermath of the upheavals of the 17th-century English Civil War, Hobbes attempted to harness people’s basic impulse of self-preservation to justify a theory of sovereignty underpinned by fear. He argued that driven by the fear of death and the aspiration for security, people would be willing to give up their freedom in exchange for the safety provided by their all-powerful sovereign. He wrote that people ‘agree to create a sovereign because they are afraid of one another’.

In one form or another, governments and policymakers have echoed Hobbes’ argument about the necessity of trading off liberty. Recently, these arguments have been used since the outbreak of the so-called War on Terror to justify limitations on civil liberty. Curbs on civil liberties are typically presented as necessary for the protection of individual citizens.

Once free speech is presented as something to be balanced and the exercise of freedom is portrayed as constituting a threat to safety, it loses its moral authority. On campuses, free speech has been equated with hate speech or denounced as a weapon of white privilege. A study published by the Brookings Institute in September 2017 indicated that 51 per cent of its American student respondents agreed with the statement that it was OK to shout down a speaker with whom they disagreed. Even more disturbing was its finding that 19 per cent of the respondents believed it is all right to use violence to prevent a ‘controversial’ speaker from speaking.

In the UK, the Policy Institute at King’s College London recently released a study of student perceptions of free speech on campus. The study highlights the loss of authority of free speech among the respondents. It reveals that 41 per cent of students agree that academics who teach material that offends students should be fired, while 39 per cent agree that students’ unions should ban speakers who cause offence. It is evident that the rise of Cancel Culture is inversely proportional to the decline of the moral authority of free speech.

Since modern times began, assertions about the necessity of trading off freedoms for an alleged benefit have been used by critics of liberty, and these benefits have turned out to be illusory. However, the belief that human dignity and a sense of self-worth require protection from the pain inflicted by hurtful speech is possibly the most counterproductive example of the trade-off argument. People acquire dignity and esteem through dealing with the problems that confront them rather than on the goodwill of the language police or a university administrator.

Trading off freedom for some alleged psychic benefit is not unlike the argument that authoritarian-minded politicians frequently employ for justifying policies that curb people’s rights to ‘preserve their freedom’. Such arguments deprive freedom – in any of its forms – of moral content. As the philosopher, Ronald Dworkin argues, ‘in a culture of liberty’ the public ‘shares a sense, almost as a matter of secular religion, that certain freedoms are in principle exempt’ from the ‘ordinary process of balancing and regulation’. He rightly fears that ‘liberty is already lost’ as ‘soon as old freedoms are put at risk in cost-benefit politics’1.

Freedom has become a second-order value

Since the emergence of modern times, freedom has tended to be a cause most supported by the left and liberals. In the 19th century, the conservative ideal of freedom tended to be more restricted and was often at the forefront of opposing the expansion of democracy. The situation has changed dramatically in the 21st century. As a commentator in The New York Times noted, ‘liberals who once championed expansive First Amendment Rights are now uneasy about them’. He added that ‘many on the left have traded an absolutist commitment to free speech for one sensitive to the harms it can inflict’

It is evident that many on the left have not only traded in their ‘absolutist commitment’ to free speech but also mutated into its opponents. As Leigh Phillips acknowledged in the leftist magazine Jacobin, ‘too many modern progressives, particularly younger ones, have become indifferent to free speech, or, worse, come to view the defense of free speech as something foreign to the Left and a weapon of oppression’.

The embrace of illiberal censoriousness by the left emerged in the 1940s. Writing in 1946, the leftist British publisher Victor Gollancz observed that with ‘freedom of speech, every other freedom is at any rate possible; without it, all are in jeopardy’. He was clearly concerned that this message had been lost on many of his left-wing friends. He wrote

‘The cry is to “outlaw fascism and anti-Semitism”: or, to put it plainly, to make the expression of fascist and anti-Semitic opinions illegal and liable to punishment. Communists are taking the lead, and the National Council for Civil Liberties has recently made nonsense of its name and objects by supporting the demand; but many non-communists of the left, and some, I regret to say, of my fellow Jews, are joining the clamour’2.

Anticipating the danger posed by Cancel Culture, Gollancz asserted that if ‘you silence fascists for fear that fascism will be established, you have already half established it by the very fact of silencing them’! Today, when anyone can be accused of being a fascist and become a target of the no-platformers, Gollancz's warning conveys a sense of dark prescience. He understood the meaning of the claim that ‘no man can be free until he has first freed himself’.

I cannot think of a better way of concluding than to end with this citation from In Praise of Freedom.

‘The sense of this little book is that freedom of the spirit is the finest attribute of a people, and that as long as it exists, even in the prison of officialdom in which the times have caught us, political and economic liberty will never quite be lost’.

Hannah Arendt would have approved.

Dworkin, R. (1996) Freedom’s Law: The Moral Reading of the American Constitution, Oxford University Press: Oxford.) p.354.

Gollancz, V. (1946) Our Threatened Values, p.30.