Fear eats the human soul and the anxieties it produces are frequently harnessed to assist the project of controlling the behaviour of people. The politicisation and instrumentalization of fear invariably encourages society to embrace the outlook of fatalism. 21st century fatalism works as a cultural orientation, an outlook that diminishes choice and diminishes subjectivity, negates the need for judgment and hollows out the meaning of responsibility.

There has never been an era since the rise of modernity where there been so many varieties of determinisms. During the Covid Pandemic it seemed as if it was no longer human society but a virus that determined the future direction of travel. Numerous experts kneeled before the altar of virus determination and declared that our lives will never be the same. On senior World Health Organisation official, David Nabarro, stated that the wearing of masks will become the new norm and that the coronavirus will not go away but will ‘stalk the human race’ for some time.

Others too piled in to insist that humanity’s fate was not in their hands and that whether people liked it or not their behaviour had to alter. As Jennifer Ashton, the author of The New Normal (2021) explained, after the Covid pandemic ‘we will never be the same again’. She added, ‘The virus has changed our world, transformed how we live, and upended our sense of normality.

At one point, Dr. Anthony Fauci- Chief Medical Advisor to the President of United States –proclaimed the death of the handshake. Fauci literally turned into the voice of the virus, constantly lecturing the public about what they could and could not do. Fauci did not simply instruct people to avoid shaking hands during the pandemic but in a hyper-fatalistic fashion asserted that people should adopt a new form of greeting, one that did not involve physical contact. He suggested that western people should emulate forms of non-physical greeting practised by Asian societies. He too projected a virus-directed ‘new normal’, one that will include ‘compulsive hand-washing and the other is the end of handshaking’.

Fauci’s New Normal is not the product of human choice but of powerful forces supposedly beyond our control. At times the fatalistic scenarios invented by public health experts verged on the grotesque. Professor Susan Michie, Director of the centre for Behaviour Change at the University College London asserted that in the aftermath of the pandemic humanity had no choice but to adopt a collectivist political doctrine. She stated that what this pandemic showed was ‘that collectivism is absolutely necessary’ She added, ‘both in a pandemic and the climate emergency, no one can go away and protect themselves. It’s not like that anymore’[v. In her scenario climate determinism effortlessly converged with viral determinism to underpin the argument that there is no alternative to collectivism.

It is worth noting that in the past members of the Communist Party like Michie, drew on arguments based on economic determinism to promote their ideals. In the 21st century there are a lot of determinisms to choose from to advance a cause. Michie’s joined-up determinism – pandemic and climate emergency- was emulated by the Prime Minister of Belgium. Alexander De Croo, who in a speech pointed to ‘Climate, Vaccines and Terrorism’ and asserted that ‘nobody is safe until everybody is safe’.

In recent times the different variety of determinisms continues to grow. Racial determinism insists that regardless of their subjective intent white people possess certain immutable characteristics. Neuro-determinism, demographic determinism reinforces the prevailing fatalistic outlook that assigns little scope for human control. Latterly Artificial Intelligence is often framed as a threat which is beyond human control. We are told that ‘Calculations Suggest It'll Be Impossible to Control a Super-Intelligent AI’.

Controlled by forces beyond human control

With such little scope for the exercise of human control it is inevitable that public life in general, and political life in particular have acquired such fatalistic form. The ‘forces of globalisation’ – often represented through the metaphor of a ‘run-away world’ – leave little room for political choice. As Phil Mullan explained in his book, Beyond Confrontation, in recent decades, arguments about the end of politics are justified by a thesis that emphasises, ‘fatalism, uncontrollability’ and the impotence of the state’.

The outlook of fatalism is strikingly expressed through the phrase ‘the right side of history’. Politicians and campaigners are not only keen to position themselves on the ‘right side’ they are also enthusiastic about castigating their opponents for being on the wrong side of history.

History has emerged as a source of legitimacy for a bewildering variety of claims and causes. Those who associate their actions and policies with the blessing of history implicitly claim a higher form of providential validation for their cause. It is a way of saying, ‘you are not only opposing me, but also the almighty figure of history’. The framing of history as a story foretold offers a new, 21st century version of Fate.

It is worth noting that the idea of history as Fate was challenged from the 16th century onwards by humanist thinkers who argued that world changed in accordance with human action rather than according to some pre-determined laws. The contemporary mystification of Fate which runs in parallel with the proliferation of determinisms is one most distinct feature of our era.

21st century Fatalism

Who decides our individual fate? How much of our future is influenced by the exercise of free will? Humanity’s destiny has been a subject of controversy since the beginning of history.

Back in ancient times, different Gods were endowed with the capacity to thwart our ambition or bless us with good fortune.

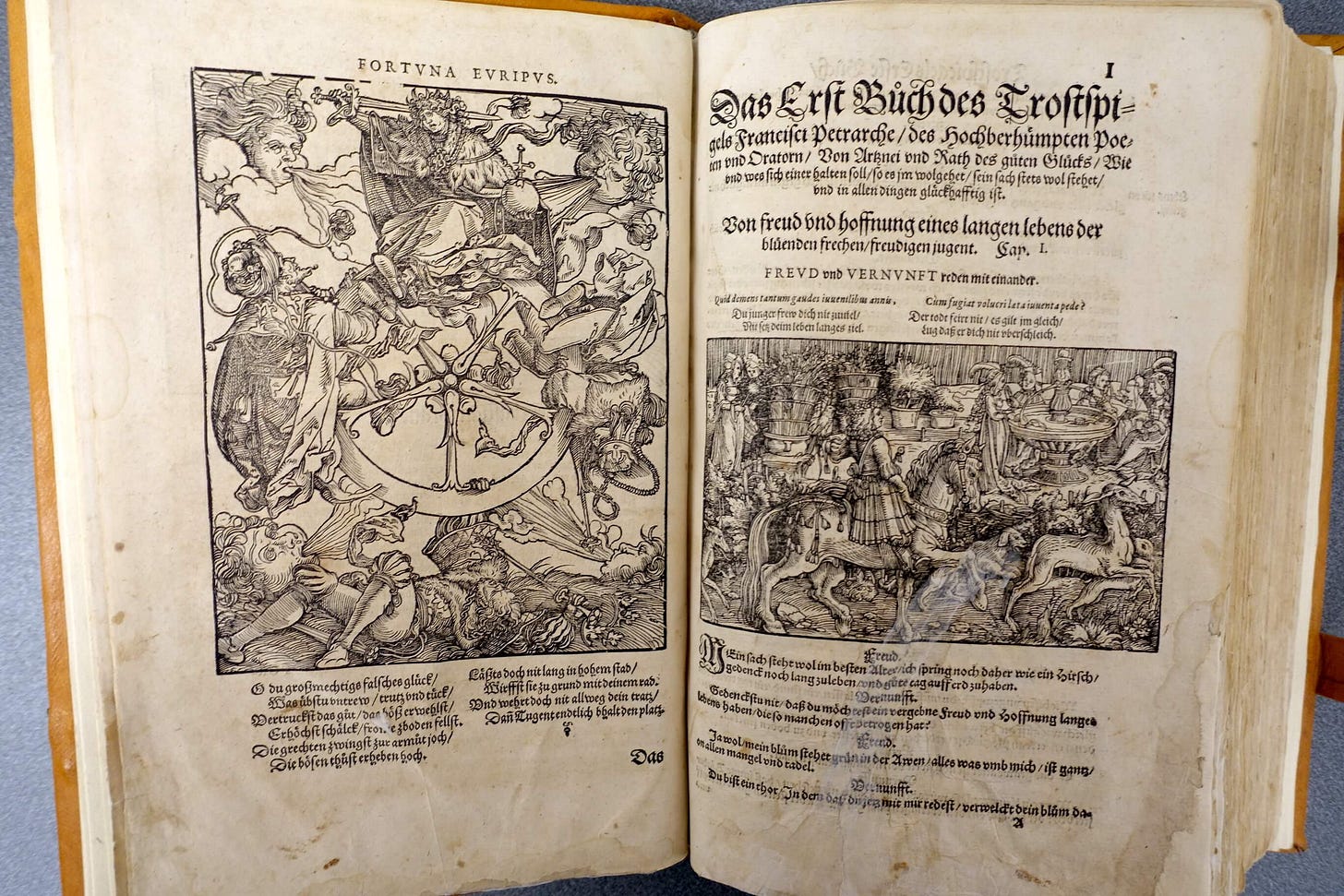

The Romans, who worshipped the goddess Fortuna, conceded her great power over human affairs. Nevertheless they still believed that her influence could be contained and even overcome by men of true virtue. As the saying goes, ‘fortune favours the brave’.

Fortuna is constantly turning the wheels of Fortune

The belief that the power of Fortune could be limited through human effort and will is one of the most important legacy of humanism. Belief in the capacity of people to exercise their will and shape their future flourished during the Renaissance, creating a world where people could dream of their ability to struggle against the tide of fortune.

Petrach’s remarkable The Remedies of Both Kinds of Fortune proposed the very modern and radical idea that humanity had the potential to control its destiny. He famously declared that:

It is more honourable to be raised to a throne than to be born to one. Fortune bestows the one, merit obtains the other.”

Petrach

A refusal to defer to fate was expressed through an affirmation of the human potential. Later during the Enlightenment this sensibility would develop into a belief that in certain circumstances man could gain the freedom necessary to influence their future. With the ascendancy of the Enlightenment and the commanding influence of science and knowledge, belief in creative and transformative potential of humanity flourished. When US President Franklin Roosevelt stated in 1939, 'Men are not prisoners of Fate, but only prisoners of their own minds' he echoed the belief that people possessed the power to make their own way in the world. That Roosevelt could express such a positive construction of the human condition in the dark days of 1939 is testimony to an admirable quality of refusing to defer to fate.

In the 21st century the optimistic belief in humanity’s potential for subduing the unknown and to become master of its fate has given way to the belief that we are too powerless to deal with the perils confronting mankind. A loss of faith in the humanity’s capacity to assume a degree of control over its destiny co-exists with a pessimistic vision of the future. In some instances, commentators go so far as to claim that humanity has no future. This sentiment is summed up by the title of James Bridle’s book; New Dark Age: Technology and the End of the Future

In his study Politics and Fate (2013) the political theorist Andrew Gamble described the mood of fatalism prevailing in society in the following terms:

‘There is now a deep pessimism about the ability of human beings to control anything very much, least of all through politics. This new fatalism about the human condition claims we are living through a major watershed in human affairs. It reflects the disillusion of political hopes in liberal and socialist utopias in the twentieth century and a widespread disenchantment with the grand narratives of the Enlightenment about reason and progress, and with modernity itself. Its most characteristic expression is the endless discourses on endism – the end of history, the end of ideology, the end of the nation-state, the end of authority, the end of the public domain, the end of politics itself – all have been proclaimed in recent years.

If one were to believe all the claims made on this score, it would be difficult to avoid the conclusion that just about everything that mattered in the days of the old normal has come to an end.

In our times Fatalism has acquired some unique qualities. In previous times debates about human destiny and how much of our Fate is predestined occurred within a moral framework where people were expected to exercise judgment and responsibility. Today fatalism works as a cultural orientation, an outlook that diminishes choice and diminishes subjectivity, negates the need for judgment and hollows out the meaning of responsibility.

Fatalism has acquired a distinct orientation in the western world. In 1962, the philosopher Richard Taylor noted that;

‘The Fatalist is usually perceived as one who treats the future just as all of us treat the past. Just as all of us believe, that we can do nothing to change or influence the past, the Fatalist believes that there is nothing that we can do to influence or change what will happen’.1

Taylor’s characterisation of the Fatalist explains well the conventional way that the temporal distinction between the past and the future was perceived.

Today, as before fatalism more or less abandons hope in society’s ability to influence its future. However, in contrast to earlier forms of fatalism, the contemporary version takes a great interest in the past. For example, numerous campaigns oriented towards putting right the injustices of the past appear devoted to fixing the historic problems of 2 or 3 centuries ago. Many initiatives designed to rid society of the traces of the bad old days by pulling down statues, altering symbols, changing language or demanding financial compensation appear far more interested in changing or influencing the past than in solving the problems of the here and now.

Of course, just because there is a growing interest in fixing the problem of the past does not mean that it is possible to change what occurred centuries ago. What past-oriented activism signifies is the redoubling of fatalism on itself!

In effect past-oriented activism breaks down the distinction between the present and the past. It creates a forever world or to be more precise a forever present. Implicitly the movement to fix the problems of the past possesses a uniquely diminished account of human subjectivity. According to this narrative people are not so much the products of the past but its victims. This trend was well captured by the sociologist John Torpey, when he drew attention to the shift from the rallying call, ‘don’t mourn, organise’ to the sensibility that we must ‘organise to mourn’ Through fossilising the self as a victim of the past responsibility for the fate of the world as it is effectively renounced.

The principal accomplishment of the redoubling of fatalism is the normalisation of irresponsibility. Its performance of reforming or transforming the past evades our responsibility for confronting the problems of our time. Worse still the tendency to erode the boundary separating us from the past leads to a mood of presentism; a mood that distracts society from looking beyond the forever present.

We need not defer to Fate. Challenging the many determinisms and the fatalistic sensibility that runs alongside it is the precondition for the revival of humanistic realism.

Taylor, R. (1962) ‘Fatalism’, Philosophical Review, 71: 56–66, pp.497-9.