Education: Has Discipline Become A Dirty Word?

Why don't we talk about the loss of authority of teachers??

One of the most disturbing developments in British schools is that teachers' authority is continually tested not just by pupils but also by their parents. I am often astonished by the vitriol and sarcasm that is directed at teachers when their attempts to enforce standards at school go awry. As I noted in my Twitter post above, teachers who take classroom discipline seriously are often attacked by parents for being oppressive or authoritarian. The attempt by teachers to create a stable learning environment is also undermined by the Ofsted inspectorate in Britain.

Below I outline an argument for taking seriously the problem of teacher authority.

Authority - the key question facing the classroom

It puzzling that that topic of the authority of the teacher is so rarely discussed as an educational issue in its own right.

The few substantive contributions on this subject - most of which were written more than a quarter of century ago -come from the philosophy of education.

Insofar as authority is considered as class-room related problem it is invariably focused on question of maintaining order and discipline.

Yet the issue of authority continually lurks in the background of the many debates about education. Debates about the national curriculum, the content of teaching, the use of mobile phones in the classroom, the system of school inspection or the professional status of teachers are all directly or indirectly related to the question of who – if anybody – possesses authority in the class-room.

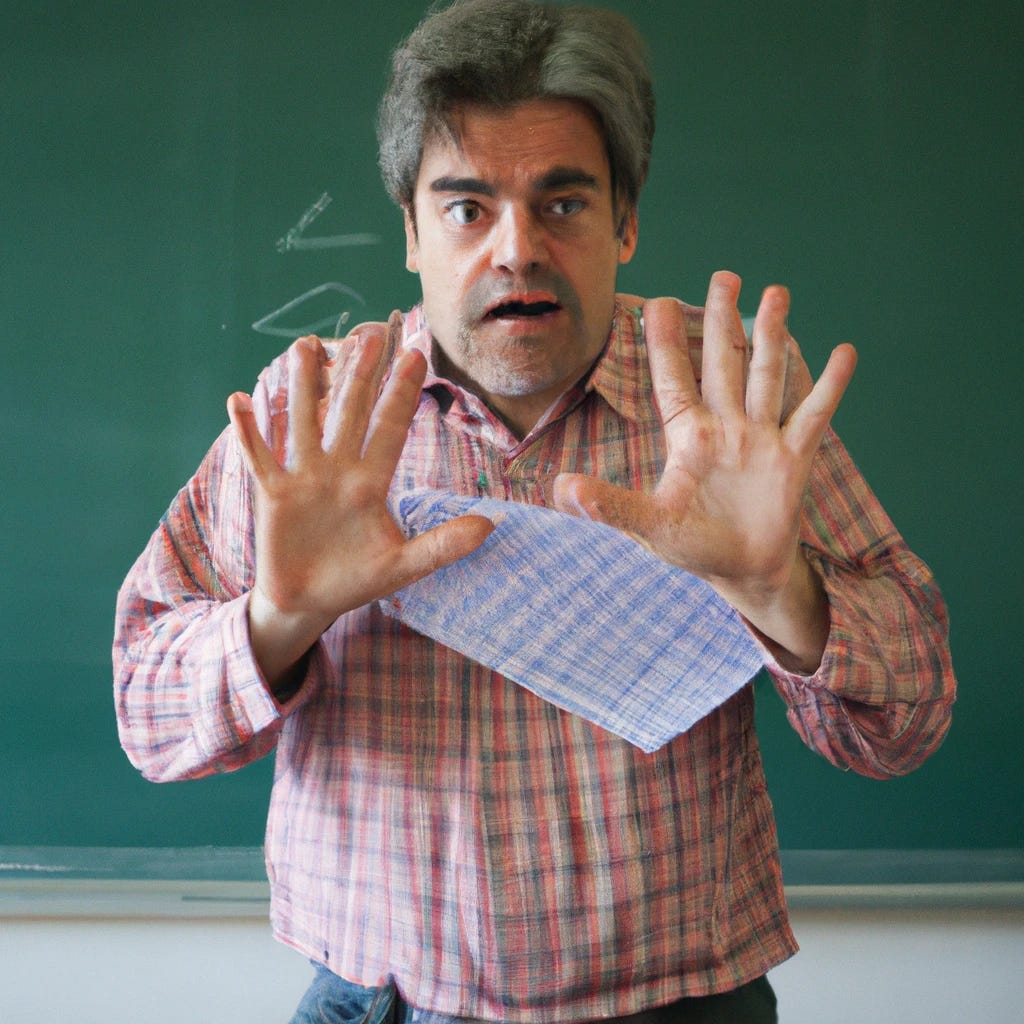

In certain instances the fragile authority of the teacher assumes a visible form. Historically the question of discipline was perceived as the problem associated with the maintenance of order in the classroom. That still remains a challenge. What has changed is that in recent times the issue of discipline is frequently perceived as a direct threat to teachers themselves. Claims by teachers unions that their members have been teased, abused and even physically attacked highlight the insecure status of some members of the profession. Probably the most striking manifestation of the helplessness of some teachers is that some cases the exercising of authority over even infants has proved too challenging. Consequently ,we now live in a world where toddlers – thankfully still a relatively small number – are suspended from school for physical or verbal assault.

As we shall see the lack of an explicit engagement with the question of authority reflects a deeply rooted tendency to evade it by either negating its importance or by recasting it as a managerial problem, for example that of classroom management. This turn towards managerial solution has importance implications for the very meaning of education. My argument is that the reliance on a technocratic approach to classroom management has influenced not just the method but the content of education.

Estrangement of Authority From Education

Back in the early 1960s the social philosopher Hannah Arendt noted that the periodic outbursts of public anxiety about the ‘crisis of education’ were an expression of a much wider cultural challenge facing society. She noted that

‘the problem of education in the modern world lies in the fact that by its very nature it cannot forego either authority or tradition, and yet must proceed in a world that is neither structured by authority nor held together by tradition’ she wrote in 1961.1

Arendt claimed that the crisis in education is often a symptom of a more fundamental erosion of authority and tradition – societies estrangement from the values of the past and its failure to reconstitute ones that are relevant to contemporary times underpins debates about education.

Arendt was one of the few observers to note that in a changing world society finds it difficult to establish a creative balance between the achievements and legacy of the past and the provision of answers to new questions and challenges thrown up in the present. It is because it so difficult to mediate between old and new that educators continually experience their professions as facing a crisis.

In the first instance the challenge facing the authority of the teacher is the outcome of a more profound societal contestation of cultural authority.2 From the early 20th century inwards – and certainly from the end of the First World War – the exercise of authority was increasingly represented as the antithesis of freedom and as potentially authoritarian. Confusions about the normative foundation of authority were internalised by educators – many of whom believed that the traditional modes of classroom interaction needed to be revised. As the philosopher of education, Geoffrey Bantock recalled in the early 1950s, ‘to understand the current uncertainty about the nature of authority in the school it is, I think, necessary to see that such indecision only reflects the doubt and confusion that exist in wider social spheres’3.

Bantock’s concern was with the ‘downgrading of the teacher’s “authority”’, which he claimed was ‘symptomatic of a waning confidence in adult values among the liberal “enlightened”. The clearest expression of the waning of confidence in adult values was a perceptible hesitancy and reluctance to take responsibility for the socialisation of the younger generations. This hesitancy was particularly widespread among progressive educators in inter-war era. As R.J.W. Selleck noted in his study English Primary Education And The Progressives: 1914-1939, this group of educators were ‘distressed and alienated’ by the values that prevailed at the time and ‘they shied away from imprinting the future generation with the marks of the present’. This sentiment was forcefully articulated by J.H. Nicholson, a Professor of Education at Newcastle University. He lamented that ‘we are an uneasy generation, most of us to some extent ill-adjusted to present conditions’ and ‘should therefore beware of passing on our own prejudices and maladjustments to those we educate’4.

Skepticism about the moral status of the prevailing values had important implications about the exercise of adult authority. It had a particularly direct impact on education. Once adult society has lost the capacity to recognize itself through the values to which it was socialized, its capacity to educate children into a new system of meaning becomes compromised. Instead of confronting the question of how to conduct essential inter-generational transactions both within and outside education there has been a tendency to evade the problem. Indeed, in many cases the erosion of the consensus about what kind of ideas to transmit to young people is perceived as proof that adults do not have an authoritative role to play in this domain. As the well-known progressive educator A.S. Neill argued, adults screwed up and ‘when we pretend to know how a child should be brought up we are being merely fatuous’5.

Uncertainty about socialisation and the status of adult authority had important implications for the professional status of the teacher. The revision or demotion of adult authority has had as its corollary the project of inflating the authority of the child. This approach is particularly explicit in the thinking of the anti-authority pedagogy that emerged in 1960s and early 1970s. In the writings of Ivan Illich or Paul Goodman the demonization of institutional authority is coupled with the deification of the authority of the child. Often the devaluation of adult authority is perceived as a move in the direction of child-centred education. However, it is more accurate to interpret this development as a semi-conscious strategy to by-pass the problems posed by the decline of adult authority. As Paul Hirst and Richard Peters have argued, the apotheosis of the ‘growth’ of the child as the motor of education ‘represents an escape from moral responsibility under the cover of a biological metaphor’. They add that ‘whether teachers like it or not a teaching situation is a directive one in which decisions about what is desirable are being made all the time’.6

Education As A Pragmatic Necessity

As Hirst and Peters contend, in the end – whatever one’s pedagogic perspective – the need for teachers authority is recognised as a pragmatic necessity. As Pierre Bourdieu argued ‘authority plays a part in all pedagogy’7 However though authority is recognised as essential for the maintenance of classroom order, it is not culturally affirmed. The relative absence of a substantive discussion and debate on the normative foundation for a teacher’s authority is symptomatic of the pragmatic orientation towards this subject.

It is important to note that the prevailing paradigm of social control posits discipline as a technical accomplishment. Its focus is on managerial techniques rather than on gaining the identification of pupils with the aims of education. Indeed the techniques of managerial control that are used in the classroom have little to do with education and its aims. Most disturbingly through its emphasis and reliance on technical manipulation it avoids a morally informed dialogue between teacher and pupil. And as Basil Bernstein reminds us – despite its rejection of hierarchical principles of authority, in practice the reliance on managerial control is arguably more authoritarian than the open exercise of authority.

For Basil Bernstein the apparently non-hierarchical classroom practices do not do away with control and hierarchy but render it invisible. He argues that invisible pedagogy establishes control through psychological techniques. He describes these as an ‘implicit hierarchy’, which is one where ‘power is masked or hidden by devices of communication’ 8The bypassing of the problem of authority through reliance on indirect forms of invisible control has been paralleled by a one-dimensional elevation of motivation as the central issue confronting education. Such approaches usually justify themselves through a child-centered narrative that claims that motivational techniques offer an instrument for harnessing pupils interests and experience

In contemporary times child-centred rhetoric serves to legitimise and indirectly reinforce the loss of an open exercise of the teacher’s authority in the classroom. Motivational techniques claim to encourage children to direct their own learning and give them a voice in the classroom. They exhort teachers to regard children as ‘intelligence agents’ or as ‘active learners’ who can from an early age ‘convert their experience into assumptions and theories about the world’. Policy-makers insist on celebrating the pupil’s voice in education and advocate ‘support for personalised learning’ In some cases children are offered the opportunity to realise themselves through happiness and emotional education. But these are essentially motivational and therapeutic techniques designed to manage behaviour. As one study noted, ‘under the ambiguities of the rubric of student-centreness, choice and empowerment, progressivist aspirations have dovetailed with managerial priorities’.9 Typically these techniques for managing behaviour are based on the premise that children respond to an initiative implemented and enforced by an adult, albeit indirectly. More often than not, child-centred pedagogy turns into an indirect form of adult control. The leading American advo, cate of progressive educationJohn Dewey specifically endorsed this approach when he argued that the teacher should ‘determine the environment of the child, and thus by indirection to direct’10.

Outwardly open, flexibly and democratic the techniques of invisible pedagogy are arguably more controlling and coercive than the ethos of discipline associated with the explicit exercise of teacher authority. As the sociologists Bourdieu and Passeron wrote:

‘To overwhelm one’s pupils with affection, as American primary school teachers do, by the use of diminutives and affectionate qualifiers, by insistent appeal to an affective understanding, etc. is to gain possession of that subtle instrument of repression, the withdrawal of affection, a pedagogic technique which is no less arbitrary, than corporal punishment or disgrace’11

The concealment of a ‘pedagogic relation’ in the guise of a ‘purely psychological relationship’ places a confusing demand on teachers who are expected to be pedagogues and therapists at the same time.

The displacement of authority with pragmatic techniques of direction has important implications for the role and status of the teacher. The authority of the teacher has two-fold dimension. It involves both theoretical and practical authority. Theoretical authority pertains to the sphere of knowledge and is founded on the mastery of an academic subject. However, theoretical authority does not simply refer to the possession of knowledge but also the expectation to be believed about beliefs of what is right and wrong. A teacher also needs to have practical authority, which is essential to ensure that learning can take place in the classroom. Through a reliance on the authority gained through the mastery of a subject teachers can project discipline as integral to its learning.

With invisible pedagogy the exercise of control becomes disassociated from the mastery of an academic subject. Its imperative of motivation is most effectively realised through the guidance of the expert in managerial control. The introduction of managerial expertise and ethos of motivation implicitly undermines the professional status of the teacher, particularly that of the subject specialist. This trend is paralleled by the tendency to subordinate the values of a subject-knowledge based curriculum to one that is principally shaped by the exigencies of motivation.

Authority and Trust

Techniques of motivation do not endow teachers with the status of trust. While the manipulative practices of invisible pedagogy can be relatively easily internalised by primary school children they have less and less of an effect on older children. Among teenagers indirect instruments of control provoke scepticism if not cynicism as they realise that they are being directed towards objectives not of their own making.

Learning in an educational environment requires trust in the authority of the teacher. When children go to school they rely on their teachers to guide them to comprehend new forms of knowledge. This reliance on the teacher involves a leap of faith which people only undertake if they accept the authority of the educator. ‘Learning always involves a determination to grasp after what is as yet uncomprehended’, observed Bantock. He added that in ‘the pupil, the act of acceptance or the authority of the as yet unknown is an essential pre-requisite to learning’.12 Indeed it is precisely because venturing out to the unknown goes so much against the inclination of children’s feelings that they need the authoritative guidance of the teacher.

However, though they may serve as the personification of the authority of a body of knowledge, a teacher’s work and behaviour is under the constant scrutiny of pupils. An effective teachers must be not only an authority in a subject but must also possess a personal capacity to act authoritatively. The possession of the personal qualities required to behave authoritatively are necessary for ensuring that pupils are willing to act in accordance with the instructions of the teacher. As Steutel and Spiecker assert ‘’without having some degree of “presence” teachers will have difficulties with keeping order in the classroom13’. This personal authority of the teacher is essential gaining and consolidating the pupils trust to leap into the unknown of finding out the answers to questions that they have not asked.

Trust in education has both an institutional and individual dimension. It presupposes confidence in the institution of education and specifically in the teaching profession. For this confidence to be converted into active trust children need to believe in their teacher’s integrity and capacity to educate them. Trust is based on a subjective assessment of the character and personality of the individual teacher. It is through a subjective relation of trust that authority ceases to be a formal or official designation and acquires its moral force. Authority which in general gives meaning to power in the context of classroom offers teachers the power to inspire belief.

So what’s the problem ?

The ambiguous status of a teacher’s authority is, as noted previously an outcome of the workings of cultural influences that are suspicious of it. However it is also the result of the internalisation of these influences within the teaching profession itself.

The tendency to confuse authority with authoritarianism, the adoption of defensive strategies that seek to by-pass the issue by embracing a child-centred approach or the pedagogy of motivation has had the consequence of undermining the professional status of the teacher further. The adoption of an invisible pedagogy has encouraged he colonisation of education by a variety of expertise. Once a the teacher’s authority became a subject of ambiguity and negotiation the status and the autonomy of the profession became compromised. Ambivalence about the moral authority of the teacher has led to the introduction of what Michel Foucault characterised as moral techniques –testing, measuring, surveillance and league tables follow. So scepticism about the exercise of authority in the classroom represents the prelude to a complicated drama which culminates with the institutionalisation of centrally orchestrated curriculum and externally imposed targets. And the public are asked to shift the focus of their trust from the teacher to the findings of the Inspector and the verdict of the league table.

My views on education are developed in my book

https://www.amazon.co.uk/s/ref=nb_sb_noss?url=search-alias%3Dstripbooks&field-keywords=Furedi+Wasted+why+education

H. Arendt (1961) Between Past and Future, Faber & Faber : London,p.193.

Its historical origins and the patterns of development are discussed in my Authority: A Sociological History, Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Bantock, G.H. (1952) Freedom And Authority In Education: A Criticism of Modern Cultural and Educational Assumptions, Faber & Faber Limited : London, p.184.

See Selleck, R.J.W. (1972) English Primary Education And The Progressives: 1914-1939, London : Routledge & Kegan Paul, p.94 and 118-119.

Cited in Selleck (1972) p.94.

Hirst, P.H. & Peters, R.S.(1970) The Logic of Education, Routledge & Kegan Paul, p.31.

Bourdieu, P. & Passeron, J.C. (1977) Reproduction: In education, Society and Culture, Sage Publications , p.10.

Social Class and pedagogic practice’ in Bernstein (2003) p.67.

Lovlie & Standish (2002) p.327.

Dewey (1956) p.18.

Bourdieu & Passeron (1977) pp.17-18.

Bantock (1952)p.189.

Steutel, J. & Spiecker, B. (2000) ‘Authority in Educational relationships’, Journal of Moral Education, vol.29 : 3, p.334.

The loss of authority of teachers is associated with adults that feel themselves threaten by their own children or pupils. To confront them and make a direct oposition , something so needy to reinforce their own caracter and growing

Up, now seems to be harmful. But for whom? Certainly nowadays to adults with the confusion between what is authority and authoritarian. Authoritarian needs to be adored by their subjects , authority requires responsability and strength to deal with hate and confronting behaves. Such more work to do that some adults escape to submit to progressive ideas from the experts of the day.

Authority requires moral content which gives those exercising it the confidence necessary to give clarity and purpose to young people. There is no need to be authoritarian which is always a symptom of a the absence of authority. The word that I prefer is authoritative - a term that implies that adults have the confidence to behave authoritatively