Do You Have A Conservative Personality? Why Do They Say That You Are Sick?

Psychology Condemns The Conservative Personality As Morally Inferior

When I read a blogger declaring ‘Conservatism is just a sickness’, I pause for breath to see whether he will go a step further and say that such ill people should be put under quarantine. The claim that conservative personality types tend to possess mental health problems and intellectual deficits is frequently asserted by psychologists and liberal academics. Such sentiments are often promoted through the mainstream media and by anti-conservative intellectuals.

As far as Hollywood, Netflix and the television media are concerned, conservatives are not nice people. Like Mr Garrison in South Park, they are not only small-minded and racist but are psychologically messed up. In typical conservative fashion, he refuses to acknowledge his emotional and psychological issues. Like many other fictional conservative characters, Mr Garrison is in denial.

Mr Garrison

Homer Simpson is a blue-collar conservative. Therefore, the producers of The Simpsons felt obliged to portray him as a bumbling and insensitive husband and father who, over the years, has turned into a self-aggrandising fool. Fortunately, Homer’s psychological deficits are compensated for by his daughter Lisa, who, because she is very liberal, must be portrayed as sensitive and emotionally literate.

The media is particularly unkind to conservative women. In the miniseries, Sharp Objects, the abusive mother, Adora Crellin, is one of the most repulsive characters you are likely to encounter. She is cast as a small-town, Southern conservative woman whose Munchausen by Proxy Syndrome has led her to poison and kill her daughter Marian.

But it is Sue Sylvester in Glee who, more than anyone else, offers an over-the-top caricature of a right-wing conservative woman. Her authoritarian personality coexists with a profound sense of personal insecurity and unrestrained narcissism. She exudes malice. That she calls for the abolition of the National Endowment for the Arts, one of the left’s favourite federal arts agencies, signals that her politics are not only wrong but also sick.

As far as media culture is concerned, conservatives possess unattractive psychological characteristics. Typically, conservatives are portrayed as mediocre and undistinguished characters who possess outdated and, often, repulsive sentiments. Though far more pervasive today than in the past, conservatism's cultural and intellectual devaluation and marginalisation have a longstanding history. To understand the cultural depreciation of the conservative mind, it is useful to look at its origins and subsequent development.

J.S. Mill, the 19th-century liberal philosopher who described the Conservative party as ‘the stupid party’, took great delight when he went further and stated that his attribution of intellectual inferiority was directed not merely at the Party but also at people who possessed a conservative outlook. When criticised for his remark, Mill replied, ‘I never meant to say that the Conservatives are generally stupid. I meant to say that stupid people are generally Conservative’.1

Since the 19th-century, Mill’s derision towards stupid conservatives has become integral to the modernist's intellectual outlook. Its claim about the supposed intellectual inferiority of conservatives often asserted that those who remained stuck in the past and insisted on retaining outdated customs and traditions, lacked imagination and the capacity to learn from new experiences. From the early 20th-century onward, it was also suggested that conservatives were incorrigibly conformist and possessed closed minds. Since affirming tradition did not require mental agility or flexibility, it was suggested that conservatives were likely to be left behind in the intellectual stakes. Many intellectuals assumed that only those who were prepared to criticise and question the existing state of society could be expected to develop a capacity for abstract and sophisticated thought.

John Stuart Mill

Until the Second World War statements about the mental deficits of the conservative mind were relatively muted. However, on balance, the experience of the inter-war years and of Second World War served to discredit the influence of right-wing and conservative intellectual traditions in Western Culture. Since the end of the Second World War right wing and conservative ideas have become marginalised within the key cultural and intellectual institutions of western society. In a frequently cited statement, the American literary critic Lionel Trilling declared in the 1949 Preface to his collection of essays, that right wing ideas no longer possessed cultural significance:

‘In the United States at this time liberalism is not only the dominant but even the sole intellectual tradition. For it is the plain fact that nowadays there are no conservative or reactionary ideas in general circulation. This does not mean, of course, that there is no impulse to conservatism or to reaction. Such impulses are certainly very strong, perhaps even stronger than most of us know. But the conservative impulse and the reactionary impulse do not, with some isolated and some ecclesiastical exceptions, express themselves in ideas but only in action or in irritable mental gestures which seek to resemble ideas.’2

Trilling’s statement echoed a view that resonated with the sensibility of Anglo-American cultural elites at the time.

Trilling’s association of the conservative mind with irritable mental gestures indicated that it had become the target of medicalisation. Similar sentiments were frequently communicated by professionals working in the fields of psychology and psychiatry. Since the late forties, the social sciences, in general, and psychology, in particular, have played an important role in providing so-called scientific legitimacy to claims about the inferior intellectual and moral status of the conservative mind.

Diagnosing the conservative mind

From the 1930s onwards, many mental health professionals assumed that right-wing and conservative emotions and attitudes served as markers for psychological problems. On reviewing this literature, it is evident that speculation about the mental deficits of conservatives was just that, speculation. It was based on the a priori assumption that respect for authority was synonymous with the instinct of authoritarianism and with a closed and prejudiced mind.

A growing literature on conservative, authoritarian, right-wing and fascist personalities assumed that individuals who were socialised by authoritarian parents would turn into adults who embraced ideals and attitudes associated with conservatism, such as patriotism, discipline and traditional attitudes toward family life. Such individuals were disparaged for not only being on the wrong side of history but were also diagnosed as ill. Conservative personality traits were portrayed as akin to symptoms of a medical condition. Conservatives were not simply politically wrong but were also ill.

The link between opinions attributed to a conservative outlook and mental illness was unambiguously expounded by Harry Overstreet, a best-selling 1950s American pop psychologist:

‘A man, for example, may be angrily against racial equality, public housing, the TVA, financial and technical aid to backward countries, organized labor, and the preaching of social rather than salvational religion… Such people may appear “normal’ in the sense that they are able to hold a job and otherwise maintain their status as members of society; but they are, we now recognize, well along the road toward mental illness’3.

By the 1950s, psychologists were busy investigating the ‘authoritarian personality’ or ‘the conservative mind’ and invariably found that the people who possessed them were mentally flawed.

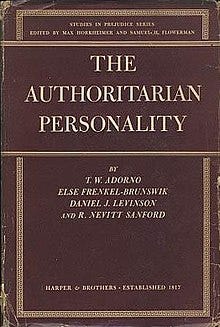

The diseasing of the conservative mind gained significant momentum with the popularisation of the Frankfurt School’s diagnosis and pathology of an authoritarian personality. Its argument was outlined in one of the most prominent and influential social science texts of the post-Second World War era, The Authoritarian Personality. This text, the work of Theodor Adorno and like-minded colleagues, claimed that there were personality traits that distinguished right-wing and potentially fascist-type individuals from democratic ones. Many of the traits that they associated with their model of an authoritarian personality were ones that are integral to classical conservative sentiments.

The experts associated with the studies that led to the publication of The Authoritarian Personality placed great emphasis on what they presented as the rigorous empirical survey that underpinned their study. Yet, though presented as a work of objective scientific research, The Authoritarian Personality should be interpreted as a moral critique of traditional forms of socialisation. In particular, its research and arguments appear to be founded on the a priori assumption that authority distorts personality development4. On inspecting the content of the studies associated with The Authoritarian Personality, it becomes evident that their authors were hostile towards family ideals and practices such as the exercise of parental discipline, the valuation of obedience and the close identification of children with their parents. Their sentiments, which pre-existed the ‘research’, were then recast through the language of science.

The study’s chapter on parents and children by Else Frenkel-Brunswik comes across as a moral critique of family life communicated through the jargon of psychology. Its argument is based on the simplistic assumption that strict parenting breeds authoritarian personality types, who then turn out to be potential fascists. According to this model, authoritarianism in the family serves as the functional equivalent of authoritarianism in public life. As in the case of medieval theories of authority – the authority of the parent mimics the political authority of the ruler.

The approach adopted by the authors of the Authoritarian Personality was to establish a model where a variety of negative traits were associated with those who score high on their F scale. (F is the abbreviation for fascist). They couple more attractive personality traits with liberal autonomous individuals, who are obviously low scorers on the F scale. According to the thesis advanced in this text, ‘conformist and conventional idealisation of parents and a sense of obligation and duty for parents’ is a marker for a high score on the F scale.

The study draws a contrast between the tendency toward ‘idealization of the parents’ as opposed to what it characterises as ‘“Objective appraisal” of parents by unprejudiced subjects’. It concludes that those who score low on the F scale are likely to be ‘more critical and realistic about their parents.’5

A few observers have criticized what they saw as a strongly politicized agenda that underpinned The Authoritarian Personality. Social critic Christopher Lasch argued that by equating mental health with left-wing politics and associating right-wing politics with an invented "authoritarian" pathology, the book's goal was to eliminate authoritarianism by ‘subjecting the American people to what amounted to collective psychotherapy – by treating them as inmates of an insane asylum.’6 During the 1950s and 1960s, the arguments advocating the thesis of an authoritarian personality helped the cause of those seeking to morally devalue conservatism. Several unattractive personality traits were added to the list of right-wing mental deficits. They were deemed to be irrational, suffering from status anxiety, and according to the sociologists David Riesman and Nathan Glazer, they were characterised by their ‘intolerance of ambiguity’.7 Often, the term conformist was used interchangeably with authoritarian. Conformist personality types were assumed to be closed-minded and, therefore, by implication, likely to possess authoritarian inclinations.

Distinctions between conformism and non-conformism and between an open and closed mind conveyed important moral and political differences. It was suggested that these differences corresponded to the distinction between the left/liberal and the right/conservative. Psychology was harnessed to legitimate the claim that the concerns of conformist right-wing people were largely an expression of emotional ‘status anxiety’. During the Cold War, leading American liberal commentators such as Richard Hofstadter and Lionel Trilling claimed that conservatism did not need to be taken seriously since it had no important argument. Hofstadter’s student, the historian Dorothy Ross recalled that the prevailing sentiment amongst fellow academics was that conservatives ‘had no mind’8. Psychological studies of personality often directed their fire against those possessing conservative psychological traits. University of Pennsylvania psychiatrist Kenneth Appel stated that conservatism was itself a personality disorder. The liberal political commentator Arthur Schlesinger Jr insisted that American conservatives were guilty of ‘schizophrenia’. Leading social scientists, such as Riesman and Hofstadter, defined ‘conservatism as a problem of abnormal psychology, a failure of intolerant, uninformed, and uneducated individuals to adjust to the complex modern world’9.

The political psychology of the conservative mind can best be understood as a form of advocacy research whose a priori assumptions are inevitably affirmed through the language of science. Through the language of science, previously identified negative political traits – authoritarianism, conformism, inflexibility, closed-mindedness – are recycled as the psychological problems that afflict the conservative mind.

Psychology’s obsession with the conservative mind

The approach adopted by The Authoritarian Personality retains considerable influence to this day. Numerous studies purport to contrast between the positive and admirable qualities of liberals and the negative and morally inferior traits of conservatives. Writing in this vein, George Lakoff divided the US electorate into two groups – those who adhere to a strict father family and those who adhere to a nurturant parent family. According to Lakoff’s schema, populists embody the outlook of the strict father family. It is their ‘strict authoritarian values’ that ‘motivate them to enter the voting booth’. By contrast, progressives are imbued with the ‘nurturant parent worldview’ and are inspired by the values of ‘empathy and responsibility.’

Many researchers in psychology have published studies that contend there is a close correlation between people’s personalities and politics. To take a representative example. Researchers at the University of Toronto ‘discovered’ that ‘the psychological concern for compassion and equality is associated with a liberal mindset, while the concern for order and respect of social norms is associated with a conservative mindset’. ‘We obtained consistent and converging evidence that personality differences between liberals and conservatives are robust, replicable and behaviourally significant’, argues one study on the ‘secret lives of liberals and conservatives’. Predictably, the liberals possess attractive traits like ‘being creative, curious and open-minded while conservatives are more conventional and orderly.’10

In recent years numerous so-called studies have published research purporting to prove the intellectual inferiority of conservative people. An example of this tendentious research is the study published by two Canadian academics last year. Titled ‘Bright Minds and Dark Attitudes Lower Cognitive Ability Predicts Greater Prejudice Through Right-Wing Ideology and Low Intergroup Contact’, it suggests that stupid simpletons go on to become prejudiced right-wingers.[xv]

Some psychologists claim that their research shows that socially conservative people feel more insecure than liberals. Others have discovered that liberals are far better at reorganising their thoughts in flexible ways than conservatives.

Advocacy research claims to have discovered that ‘religious conservatives make poorer moral decisions than liberals’.[xvii] Some psychological studies have concluded that liberals and conservatives differ in cognitive style. As you would expect, liberal cognitive styles are far more attractive than those of their conservative peers. ‘Liberals are more flexible, and tolerant of complexity and novelty, whereas conservatives are more rigid, are more resistant to change, and prefer clear answers’. Liberals also possess greater ‘neurocognitive sensitivity’ to cues than their far more rigid conservative counterparts11.

The representation of conservatives as less intelligent than their left-wing counterparts is frequently communicated by ‘research’ on the so-called conservative syndrome. This syndrome hypothesises that conservatism and low cognitive ability are directly correlated.12

A commentator in the progressive magazine Mother Jones wrote in 2014, ‘Ten years ago, it was wildly controversial to talk about psychological differences between liberals and conservatives. Today, it’s becoming hard not to’13] As it happens, this commentator gets it totally wrong. For decades, discussing the psychological contrast between liberals and conservatives has been far from ‘wildly controversial’.

Does all this matter?

The psychological devaluation of conservatism plays a significant role in influencing how people perceive political life. It is important to realise that the language of psychology permeates all dimensions of public life. Psychological values have displaced moral ones; arguably, the therapeutic ethos provides the normative framework through which individuals make sense of themselves. Its pronouncement matters, and its diagnosis of the conservative mind brands it with the stamp of intellectual and moral inferiority.

Once outside the psychological laboratory, this science serves as a cultural weapon used to invalidate the moral status of conservative-minded people. As Mark Proudman stated:

‘The imputation of intelligence and of its associated characteristics of enlightenment, broad-mindedness, knowledge and sophistication to some ideologies and not to others is itself therefore a powerful tool of ideological advocacy.’14

Making fun of the ‘outdated’ views of conservative people and exposing their traditional ways to ridicule is one way of assuming the status of moral superiority. Using the authority of science to legitimate this ridicule further, strengthens this claim of moral authority.

Psychology plays an important role in the workings of 21st-century anti-conservative ideology. It provides important intellectual resources for the construction of unattractive conservative stereotypes. In an age where identity really counts, it continually seeks to devalue and de-legitimate the identity of a conservative. Contesting psychology’s stereotype of the conservative mind is long overdue.

John Stuart Mill, ‘Autobiography [1873]’, in John M. Robson and Jack Stillinger (Eds) Collected Works, v. i (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1981), p. 274.

Trilling, L. (1957) ‘The Sense of the Past’ in the Liberal Imagination, Doubleday Anchor Books: New York.p.ix.

from Overstreet, H.A. (1952) The Great Enterprise: relating Ourselves to the World, Norton: New York, p.115.

Adorno, T.W., Frenkel-Brunswik, E., Levinson, D.J. and Sanford, R.N., (1969) The authoritarian personality, W.W. Norton & Company: New York

Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik & Sanford (1969) p.340.

Lasch, C. (2013) The True and Only Heaven: Progress and Its Critics, Norton: New York p.44.

Cohen-Cole, J. (2014) The Open Mind: Cold War Politics and the Sciences of Human Nature, The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, p.51

Cohen-Cole (2014) p.51.

Dowbiggin, I. (2011) The Quest Form Mental Health: The Tale of Science, Medicine, and Mass Society, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge) pp.138-139.

Carney, D.R., Jost, J.T., Gosling, S.D. and Potter, J., 2008. The secret lives of liberals and conservatives: Personality profiles, interaction styles, and the things they leave behind. Political Psychology, 29(6), pp.807-840.

Maturity, M., 2012. Moral Identity versus Moral Reasoning in Religious Conservatives. The Humanistic Psychologist, 40, pp.343-363.

See http://davesource.com/Fringe/Fringe/Politics/Conservatism-and-cognitive-ability.pdf

https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2014/07/biology-ideology-john-hibbing-negativity-bias/

Proudman, M.F., 2005. ‘The stupid party’: Intellectual repute as a category of ideological analysis. Journal of Political Ideologies, 10(2).

p.206.