Woke Is Not The Problem – It Is The Symptom Of Something Far Worse

It is the disturbing trend towards decivilization that should concern us

Not sure if you have heard of the term decivilization.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines decivilization as ‘The process or condition of losing civilization’.

The OED’s first citation of this term refers to an article in The North American Review in November 1878. Since that time the term has been rarely used. Why? Because for many it is difficult to come to terms with the fact that alongside our civilised pretensions society is also prone to suffer from the malaise of decivilization.

Kenneth Clark in his fascinating Civilisation (1969) associated civilisation with ‘a sense of permanence’.

He added that, a ‘civilised man, or so it seems to me, must feel that he belongs somewhere in space and time; that he consciously looks forward and looks back’[i]. As I noted on several occasions in Roots & Wings, Western culture has adopted a profoundly presentist outlook and neither looks forward nor looks back[ii]. The sense of permanence has given way to its very opposite; transience, temporariness and ephemerality.

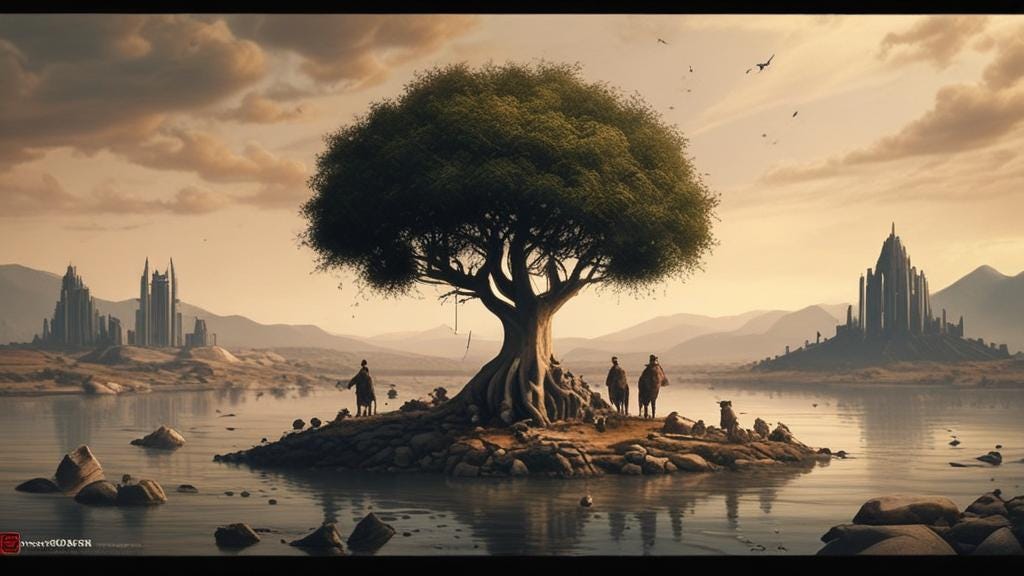

Throughout human history the sense of permanence served as a precondition for allowing people to dream of the possibility of creating something that was durable and built for the future. Based on the foundation of a shared past societies possessed a form of consciousness that encouraged the attempt to build a temporal bridge between the present and the future.

Without a sense of permanence there is little incentive to settle down, develop agricultural societies or build temples and cities. The prerequisite for the development and the reproduction of a sense of permanence is the cultivation of an organic connection between the present and the past. This civilisational accomplishment is essential for endowing human existence with meaning and for the development of stable social and individual identities. In contrast decivilization flourishes in historical moments when communities struggle to endow their existence with meaning.

Decivilization should be understood as a process – both conscious and unconscious – through which the connection between the present and the past is ruptured and the sense of permanence diminishes. Over time the sense of permanence has diminished to the point that it is overwhelmed by the consciousness of constant change. In the current era this trend has gained momentum and directly influences the zeitgeist. Today it is transience and novelty rather than permanence that dominates the human imagination.

The consciousness of change

The diminishing of the sense of permanence has been inversely proportional to the ascendancy of the consciousness of change. Today it often seems that if anything is permanent it is the permanence of change. The perception that culture is discontinuous influences the behaviour of public life. This perception is underpinned by the transformation of the idea of ceaseless change into a veritable fetish. For over a century generation after generation were told and believed that their era is uniquely one of unprecedented rapid change. The perception of rapid change goes hand in hand with the tendency to declare previous cultural accomplishments as outdated and obsolete.

This condition of cultural discontinuity is constantly reproduced by an inflated sense of rapid change. The constant references to rapid change over the past 150 years indicate that this perception has acquired a life of its own and as the sociologist Daniel Bell pointed out ‘overshadows the dimensions of actual change’[iii]. The consciousness that corresponds to this sensibility assumes that the new necessarily represents an improvement over the old. This attitude is not only attached to technologies and their products but also towards values. What follows is ‘ceaseless searching for a new sensibility’.[iv]

The discontinuity of culture coexists with the loss of the sense of the past. The loss of this sensibility has had an unsettling effect on culture itself and has deprived it of moral depth. A consciousness of culture as unsettled and discontinuous renders it volatile. Inner tensions within culture are refracted through what the social critic Lionel Trilling characterised as the ‘acculturation of the anti-cultural’. Cultural discontinuity has in some cases led to the negation of its previous premise.

In 1961, when he penned these words, Trilling’s remarks were directed at the uncritical cultural criticism that prevailed among his university students. Today, the acculturation of the anticultural exercises a powerful role over the imagination of western society. Culture is frequently framed in instrumental and pragmatic terms and rarely perceived as a system of norms that endow human life with meaning. Culture has become a shallow construct to be disposed of or changed. Calls for ‘changing culture’ are casually and regularly echoed in management circles and by policy makers. ‘The Fastest Way To Change A Culture’ advises a commentator in Forbes [v]. Apart from references to aboriginal exoticized people, culture tends be a target of change rather than preservation.

One of the by-products of the consciousnes of change was a re-definition of culture itself. It has become downgraded, rendered shallow and deprived of normative content. Phrases like a ‘culture of bullying’, ‘negative organization culture’, ‘toxic work culture’ or a ‘canteen culture’ both trivialise and render culture meaningless. Typically, this usage of the term culture serves as an invitation to changing it to, for example, a ‘culture of learning’ or an ‘inclusive workplace culture’. The acculturation of the anticultural and the spirit of the counterculture are integral features of the contemporary zeitgeist. Cultural norms and attitudes that emerged as a reaction to those of the past soon suffer the same fate and are cast aside by the latest version of adversary culture. Bell observed;

‘Today, each new generation, starting off at the benchmarks attained by the adversary culture of its cultural parents, declares in sweeping fashion that the status quo represents backward conservatism or repression, so that, in a widening gyre, new and fresh assaults on the social structure are mounted’[vi].

An illustration of this trend is the reaction of different waves of feminism to one another, in particular the tension between the second and fourth wave of feminism[vii].

The western elites do not perceive cultural discontinuity as a problem. In their vocabulary, terms like fluidity, flexibility, reinvention, disruption have connotations that are entirely positive. That is why they can so casually dismiss those who perceive discontinuity as a problem as suffering from nostalgia for permanence. That is also why they do not feel that they have a meaningful connection with a civilisation.

For most people cultural disconnection constitutes a serious existential problem. Estrangement from the past encourages a regime of disconnection between people in the present. The condition of anomie and alienation, which was already identified as a pathology by commentators in the 19th century has acquired far greater depth today. That is why for millions of people the quest for meaning has become the ever-present condition of their life. Decivilization deprives communities of a web of meaning through which they can make sense of their predicament.

Decivilisation runs in parallel with the development of an orientation of contempt towards the past. This sentiment is frequently echoed through the exhortation to break with the past. More than anything else the constant calls to break from the outdated ways of the past captures the temper of decivilization. The main mission of decivilization is to de-legitimate the historical achievements of humanity in all its different magnificent forms. This sentiment is most systematically articulated by precisely those who were traditionally charged with responsibility for serving as custodians of civilisation; the cultural establishment.

The western cultural elite is distinctively uncomfortable with the narrative of civilisation and has lost its enthusiasm for celebrating it. The contemporary cultural landscape is saturated with a corpus of literature that calls into question the moral authority of civilisation and associates it with negative qualities. Numerous influential publications decry the very idea of civilisation, particularly in its western form. Commentaries use the term – the ‘myth of civilisation’ to signify their rejection of the idealisation of civilisation. Such commentaries are paralleled by a studies which exude a profound sense of hostility towards the past. Their polemic directly targets narratives that offer a positive representation of the achievements of Greek, Roman and European civilisations.

The project of detaching the present from the past has important implications for the constitution of Identity. Without the stability provided by a sense of permanence the achievement of identity is fraught with difficulty and susceptible to its politicisation. De-civilization means that even the most foundational identities- such as that between man and woman – is called into question.. At a time when the age-old distinction between humans and animals is queried even the answer to the question of ‘what it means to be human’ becomes complicated. It is in such circumstances – where the taken-for granted assumptions of western civilisation lose their salience – that the sentiments associated with wokism flourish.

Countering the threat posed by the trend towards de-civilization represents the most important challenge of our time.

In the next few weeks we shall explore the meaning of western civilisation and why its defence is essential for human civilisation

[i] Clark, K. (1969) Civilisation , (BBC : London) pp.14,17.

[iii] Bell (1972) p.12.

[iv] Bell (1972) p.12.

[v] https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidrock/2019/05/24/fastest-way-to-change-culture/?sh=4cda0763d50c

[vi] Bell (1976) p.41.

[vii] See https://www.vox.com/2018/3/20/16955588/feminism-waves-explained-first-second-third-fourth and Cook (2011).

Excellent essay. Decivilization and presentism, two of the most serious existential threats to our success as a species. Another, I believe is the denialism of basic innate human nature by deeply unintelligent, self proclaimed authoritarian elites, and the disastrous consequences evident throughout true history. They don’t get to play God without things ending very badly.

I’ve often thought of civilization as a system of “encoding reality” much like cognition in a Friston framework. Time causes model drift as cultures touch each other, and the usually required energy expenditure to expel entropy keeps the wheels on the train. When the energy required to maintain integrity grows above a certain point the civilization cannot maintain coherence and dissolves into another model, or anarchy, or disease and death of the constituent standard-bearers.

Current Western civilization has vast resources available to expel entropic change, more so than any time in history. Witness the bounce-back from COVID. What’s daunting is the lack of insulators in current civilizations models - internet, television, and global network infrastructure raises the “temperature” of information entropy far more effectively than before and the thermal bath of high entropy “variations” of cultural encodings of reality are affecting people’s ability to keep a coherent version of culture in their minds.