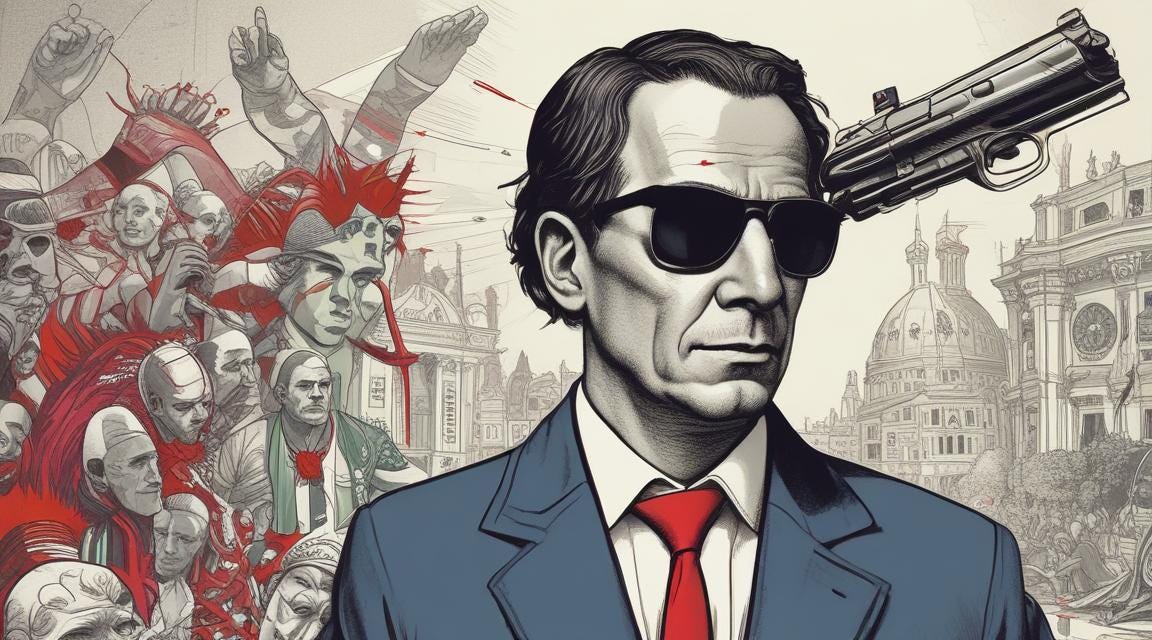

The Western World is blighted by an unprecedented level of political, social and cultural polarisation. These days political differences are regarded as a causus belli: a provocation for the declaration of a war. People that were once described as political opponents are often described as enemies. The attempt to assassinate Donald Trump is the inexorable consequence of the zeitgeist of polarisation.

To be sure there have been numerous acts of political violence and attempts to assassinate American presidents and presidential candidates in the past. But this assassination attempt occurs in a very different historical context. Previous acts of violence- such the attempt to kill President Reagan or the assassination of Robert Kennedy – occurred at a time when America was relatively united. Unlike now, supporters of the target of an assassination attempt did not point the finger at political opponents. Unlike now there were no calls to hit back at the other side. Unlike now, Americans as a whole, did not feel unsafe.

Today’s polarised environment is the product of the lethal synthesis of political and cultural differences. The politicisation of culture has led to a situation where fundamental differences in value continue to spiral out of control. As I explain below, they are spiralling out of control for the simple reason that cultural conflicts have an immanent tendency to intensify and expand the range of their targets.

Obviously, most sensible people on both sides of the political divide are horrified by the attempt to assassinate Trump. Most sensible people decry any acts of political violence.

But there are far too many people who cannot empathise with the predicament faced by their opponents. Encouraged by the mainstream media they describe their opponents as fascists, far right, hard right or extreme right. These caricatures have become so deeply embedded in some that they can no longer distinguish between reality and their political fantasy.

The German comedian El Hotzo who responded with the post on X that stated ‘I think it is absolutely fantastic if fascists die’ is thankfully part of a small minority of nihilistic culture warriors. But just remember that the responsibility for what has occurred are all those institutions and elites who have weaponised culture to assist their domination of society.

The Weaponization of Culture

Disputes about competing values, lifestyles and perceptions of cultural threat have come to dominate public life. The political vocabulary that has served western societies in the 19th and most of the 20th century has become exhausted and has been displaced by the idiom of culture. Even disputes that were once conveyed through the rhetoric of class, social injustice or ideology tend to come alive only when communicated through the grammar of culture. The target is no longer the rich but old, white, stale, posh men. The focus is toxic masculinity or white privilege and not a system of economic domination.

During its current phase, the culture war encompasses virtually all areas of everyday life. It has encouraged an unprecedented level of polarisation over matters that once would have been seen as non-political. That is why today just about anything, from the food you eat to the clothes you wear, can become a subject of vitriolic argument.

Conflicts over values have acquired an enormous significance in political life. Recent debates on abortion, euthanasia, immigration, gay marriage, trans pronouns, whiteness and family life indicate that there is an absence of consensus on some of the most fundamental questions facing society. The contestation of norms and values has politicised culture to a profound degree. Even people’s personal decisions, including who one chooses to have sex with or the food you eat are interpreted as political statements.

The personalisation of politics can be interpreted as an example of what the German sociologist Max Weber called the ‘stylisation of life’. Through the embrace of styles, people set themselves apart, reinforce their status and draw a moral contrast between their styles of life and those of others. As Pierre Bourdieu, in his influential essay Distinction, noted, ‘aesthetic intolerance can be terribly violent’. Struggles over the ‘art of living’ serve to draw lines between behaviour and attitudes considered legitimate and those deserving of moral condemnation. The fury with which the culture war is fought out on social media over trivial matters such as one’s hairstyle or taste in fashion speaks to the unrestrained emotionalism at work these days.

Twenty-first-century cultural conflict is waged over the art of living. In universities, this trend is apparent in the numerous conflicts over cultural appropriation. The outbreak of rows over the consumption of culturally insensitive food or the wearing of inappropriate clothes shows that nothing is too trivial or too personal to constitute a political battleground today.

Increasingly, in the culture war, hostility is directed less at people’s beliefs than at people’s cultural identity. This can be seen in the project of pathologising male identity as ‘toxic masculinity’, or of stigmatising white people through the self-serving concepts of ‘whiteness’ and ‘white fragility’, both of which assume white people to be inherently racist. The politicisation of identity in this way is divisive and gives all arguments an intensely emotional force. What in another context, Freud described as the ‘narcissism of minor difference’ has acquired a ubiquitous presence in western societies.

Conflicts over values are potentially much more deadly than conflicts over material possessions or wealth.. It is always possible to come to a sensible compromise over the way that material resources are divided up or the way that political offices are distributed. Values express a person’s identity and beliefs to the point that if they are not affirmed an individual may experience it as a slight on their persona or as an existential crisis. That is why conflicts involving religion, value or moral claims are rarely resolved through compromise.

One of the most memorable expressions of the intensity of this politicisation of lifestyle occurred in April 2008 when during the American Presidential Campaign, Barack Obama gave his ‘Bittergate’ speech. This was the name given to the controversy caused by Obama’s remarks at a fundraising event in San Francisco. Obama was talking about his difficulty in winning over white working-class voters in the Pennsylvania primary, when he said: ‘[It’s] not surprising they get bitter, they cling to guns or religion or antipathy to people who aren’t like them or anti-immigrant sentiment or anti-trade sentiment as a way to explain their frustrations.’ This casual and knowing putdown of small-town folk sent a very clear message about the cultural fault-line that divides America today. He is blue (Democrat and liberal), they are red (Republican and traditionalist); he is enlightened, they are bitter.

What underpinned Obama’s contemptuous description of the small-town folk of the Rust Belt is the conviction that they inhabit a different moral universe from that of enlightened America. This is a language that at once asserts the moral authority of the speakers and dehumanises their moral inferiors. Tragically the language of dehumanisation habituates its users to become desensitized and estranged from civilised behaviour and the values associated with it.

Some of those people in Pennsylvania who Obama demonised in 2008 as bitter were in attendance at the scene of the assassination attempt against Trump. No doubt they now realise that there are now Americans who do not regard them as fellow citizens. One wonders if they feel that they belong to a different nation to those who treat them as members of an alien culture. They like, millions of other sensible people are entitled to feel bitter.

The German comedian who rejoiced at the attempt to assassinate Trump eventually deleted his post. He soon realised that such an enthusiastic public affirmation of political murder is not a good look. But tragically when you regard political opponents as your enemy and demonise their values than civilisational standards become negotiable. Dehumanisation of the other leads to a selective attitude towards the valuation of human life. Unfortunately, there are far too many people who quietly shared El Hotzo’s celebration of political violence.

El Hotzo is the product of the curse of intolerance that afflicts society on both sides of the Atlantic. The mere invocation of the slander of being ‘fascist’ or ‘far right’ serves as a prelude from being treated as a lower form of human being. Taking a stand against their crusade of intolerance is the precondition for upholding the standards of civilized political behaviour.

Yes, too true of fortunately only a minority on the left.

Frank

Keen insight.

Rejection of Christian teachings have destructive implications.

How many now remember/agree with this teaching that known to western world (and sometimes applied)?

“You heard that it was said: ‘You must love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’

However, I say to you: Continue to love your enemies and to pray for those who persecute you,

so that you may prove yourselves sons of your Father who is in the heavens, since he makes his sun rise on both the wicked and the good and makes it rain on both the righteous and the unrighteous.’’

He wasn’t promoting ‘unrighteousness’, he was expecting followers to ‘prove themselves’ righteous by ‘loving their enemies’.

Who now believes that?

Christianity is intolerant?

What a travesty!

Thanks

Clay