Moral Neutrality and Irresponsibility afflict public life

The fear of judgement threatens public life in the West

Judgy

A healthy democratic public life depends on citizens engaging with one another, arguing, debating and questioning each other. During such an interaction, people judge the behaviour and ideas of other members of the public. It is through the exercise of judgment that decisions about the welfare of a community are enacted, and differences of opinion are clarified. Without judgment, politics mutates into a technical process of bureaucratic decision-making. It is through judgment that moral life comes into its own; in its absence, moral indifference can corrode public life.

At some point in the second half of the 20th century, the act of judgment came to be represented in Western culture as something to be feared and avoided. Individuals castigated for their judgmental behaviour were associated with unpleasant and disturbing character traits. Someone perceived as judgy was portrayed as morally inferior to those who acclaimed their refusal to judge.

By this point, the non-judgemental personality emerged as a cultural ideal and schoolchildren are now educated to adopt it as a desirable character trait. Teachers are encouraged to adopt so-called non-judgmental pedagogy to the point of exhorting the profession to avoid criticism in the classroom.

By the 1960s, the creative public act of judgement was increasingly portrayed in negative terms. People were taught to avoid it since it was now seen as a character flaw that signified a personality defined by insensitivity and narrow-minded prejudice. Indeed, the distinction between prejudice – a judgement based on preconceived notions – and judgement in general gradually became blurred.

The tendency to condemn the act of moral judgment was justified by the claim that this form of behaviour is harmful to those subjected to it. Initially, the claim that judgement caused psychological harm focused on children and individuals suffering from mental health problems. Teachers and adults were instructed to desist from criticising children, even if they misbehaved or failed to complete their assignments in class. Progressive pedagogy prided itself in its refusal to judge.

Since the 1980s, the crusade against judgement has acquired a powerful dynamic. The main driver of this trend is the growing influence of the view that people, especially children, lack the resilience to deal with judgement: a belief widely advocated by parenting experts and early years educators. Schoolteachers are trained to avoid explicit criticism of their pupils and practice techniques that validate classroom members. The sentiment that ‘criticism is violence’ has gained significant influence on university campuses and among society’s cultural elites. Judgement is sometimes depicted as a form of psychic violence, especially if applied to children: the sociologist Richard Sennett echoes this sentiment when he writes of the ‘devastating implications of rendering judgement on someone’s future’. Some even go so far as to claim that ‘judgmental behaviour can have long-lasting adverse physical and mental health effects’.

Insulating people, especially children, from the supposed harms of judgment has become something of a cottage industry. The charity, Pets as Therapy, advocates using dogs to reduce stress in prisons and elsewhere on the ground that these animals are ‘non-judgmental’. Therapy animals are also used to help children to learn to read on the grounds that the ‘non-threatening and non-judgemental presence of a dog may improve a children’s feelings of support during reading’.

Non-judgmental therapy dog

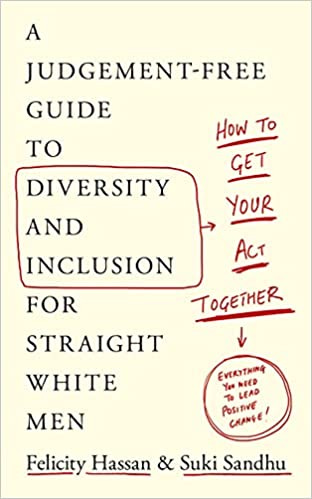

The coupling of non-threatening and non-judgmental is significant, for it assumes that the act of judgment threatens its intended recipient. In the contemporary vernacular, the term judgmental always conveys negative characteristics. Consequently, reassuring people that they will not be subjected to judgment has become widely practised cultural affectation. The self-help industry frequently advertises itself as non-judgemental. Take a few book titles as examples of this trend; How to Get Your Act Together: A Judgement-Free Guide to Diversity and Inclusion for Straight White Men, or Birth Without Fear: The Judgment-Free Guide to Taking Charge of Your Pregnancy, Birth, and Postpartum,or Women with Money: The Judgment-Free Guide to Creating the Joyful, Less Stressed, Purposeful (and, Yes, Rich) Life YoDeserve.In these instances, the promise of a judgment-free guide is meant to reassure and offer the guarantee that you will not be made to feel uncomfortable.

Safe space - a refuge from judgment

The quest for a judgment-free environment led to the popularisation of the idea of a safe space. The main driver of the safe-space movement is the aspiration to be quarantined against criticism and judgment. In universities, where it was first popularised, the demand for safe space was justified on the grounds that, since people are vulnerable and emotionally fragile, they need to be quarantined from the toxic effects of criticism and judgment.

The concerns voiced by safe space advocates were not so much directed at protecting physical security but at threats directed at their psyche and identity. At times campaigners for safe space flaunt their vulnerability and fragility to justify their demand for protection. The imperative of insulating human fragility from the emotional pain caused by offending words and criticisms continued to play a role even at the height of the Covid pandemic. Numerous calls for safe spaces during the pandemic drew attention to the need for a space where they could feel comfortable and conduct their affairs without being judged. ‘Having a space where LGBTQ people can simply exist in their own skin and experience, without judgment or pressure to hide for the benefit of cisgender, heterosexual people, can be enormously beneficial,’ wrote one LGBTQ advocate in May 2020.During the pandemic, statements drawing attention to the benefits of safe spaces invariably praised their non-judgmental ethos.

When I carried out a content analysis of documents calling for safe spaces in 2016–17, I was struck by the regularity with which the avoidance of judgment featured as their key objective. In effect, a safe space provides a quarantine from the threat of judgment. That is why from this perspective, free speech and robust debate are often diagnosed as unsafe and a danger to mental health. Supporters of safe spaces regard the absence of judgment as one of the most cherished features of this institution. This point is explicitly recognised by many universities that advertise their commitment to the core value of non-judgmentalism. The Student Services Value Statement of St Andrew University promises to ‘actively reflect’ on its ‘practice to ensure our environment is non-judgemental’. Universities regularly portray their safe spaces as havens from judgment. ‘Safe Zone provides an avenue for LGBTQ individuals to be able to identify places and people who are supportive, non-judgmental, and welcoming of open dialogues regarding these issues’, declares Montana State University in its advert for its Safe Zone.

The cultural precondition for the idealisation of safety as the foundational value of society and for creating the demand for safe spaces was the devaluation of courage and judgment. Judgment plays an essential role in helping people manage uncertainty and calculate risks. It allows us to deal with our fears sensibly. Paradoxically, this important weapon for managing fear has become a focus for fear. The fear of judgment has become normalised as a threat to people’s well-being and safety. And a safe space that serves as a quarantine from judgment has emerged in response to this fear.

The assimilation of non-judgemental and affirming therapeutic sensibilities by higher education has important implications for the conduct of its intellectual culture. Not judging is now perceived as a positive virtue that enhances students' learning experience. And that is a problem for anyone who takes seriously the ethos of liberal university education. That the act of human judgment, which has been historically linked to the making of moral and political choices and intellectual development, is now regarded in such a negative light is testimony to the university’s estrangement from humanist values and critical reflection.

From the standpoint of a liberal humanist approach to education and intellectual life, judgment is not merely a responsible response to other people’s beliefs and behaviour: it is a public duty. Citizens who judge one another demonstrate that they take each other’s ideas seriously to the point of reflecting on them, assessing their strengths and weaknesses and criticising them. Without judgment, an open and honest dialogue between people becomes impossible. Drawing on Kant’s Critique of Judgment, Hannah Arendt wrote of an ‘enlarged way of thinking, which as judgment knows how to transcend its own individual limitations’. Exposure to judgment challenges us – and yes, sometimes makes us very uncomfortable – but it also helps us understand our arguments' strengths and weaknesses and learn from each other’s experiences.

Arendt characterised the reluctance to judge as an expression of a disinclination towards public association. She wrote of the ‘blind obstinacy that becomes manifest in the lack of imagination and failure to judge’. From a humanist perspective, judgement is not simply an acceptable response to other people’s beliefs and behaviour, but a public duty, which establishes the basis for dialogue between an individual and others. The current endowment of the act of judgement with overwhelmingly negative qualities is premised on the view that this act discriminates, excludes, and in some cases, harms those judged. Instead of perceiving the act of judgement as a deed through which people can establish connections and develop a shared understanding of one another’s outlook, its critics depict it one-sidedly as a source of conflict. But contrary to the claim that judgement closes discussion, ‘the power of judgment rests on a potential agreement with others’, states Arendt. Judging plays a central role in disclosing to individuals the nature of their public world: ‘judging is one, if not the most, important activity in which this sharing-the-world-with-others comes to pass’

Non-judgementalism discourages society from discussing issues that implicitly raise questions about right and wrong. The French philosopher Marcel Merlau-Ponty wrote that ‘a truth always means that someone is judging’.[xvi] The quest for truth is undermined when a society is reluctant to encourage judgement. The positive potential of an act of judgment depends on the degree to which it is based on experience, reflection and impartiality. Not all judgements are of equal worth, and, as Arendt remarks, the quality of a judgment ‘depends upon the degree of its impartiality’. But partial and hasty evaluations are not an argument against judging, only for adopting a more responsible attitude towards it.

The philosopher Mary Midgley points out that judging makes it possible for us to ‘find our way through a whole forest of possibilities’.[xvii] Freedom itself is based on the human potential for action; without the exercise of judgment, freedom itself becomes denuded of moral content. The sociologist Zygmunt Bauman grasped the implications of the sacralisation of non-judgementalism when he warned about the trend towards what he called ‘adiaphorization’: the exemption of a considerable part of human action from moral judgement and, indeed, moral significance.

One of the few occasions when adiaphorization, or moral indifference, turns into its opposite is when it is confronted with those who take moral boundaries seriously. Those who persist in making distinctions and drawing lines are condemned for failing to embrace the openness of non-judgementalism. Those deemed ‘judgemental’ are unambiguously judged as not worthy of respect. This response indicates that even the most zealous advocate of non-judgementalism cannot entirely abandon judgement. Appearances to the contrary, the ethos of non-judgmentalism is almost always implicated in judgment. However, it is rarely able to acknowledge its role and tends to associate the act of judgment with individuals and groups on the other side of the cultural divide.

The reluctance to judge is the flip side of avoiding taking responsibility. Those who supposedly do not judge do not have to take responsibility for their judgment. That is why in public life, non-judgmentalism and irresponsibility run in parallel with one another.

Frank Furedi, What’s Happened to The University? A Sociological Exploration of its Infantilization (New York: Routledge 2017), Chapter 4, “Safe Space”.

For a discussion of the consequences of the loss of judgment see Frank Furedi (2020 Why Borders Matter : Why Humanity Must Relearn the Art Of Drawing Boundaries, Routledge : London.

Bauman (1996) p.32. The term adiaphorous means something that is neither good or bad. It conveys the meaning of indifferent or neutral. For Bauman, adiaphorization refers to systems and procedures that hep to detach the evaluation of issues from the domain of morality. It implies the institutionalisation of moral indifference.