Democracy Is In Serious Trouble!

Across The Political Divide The Different Political Factions Regard The People As At Best Voting Fodder And At Worst As A Threat To Social Order

Across The Political Divide The Different Political Factions Regard The People As At Best Voting Fodder And At Worst As A Threat To Social Order

Dear friends and subscribers. I have good and bad news. The good news is that I finished the first draft of my new book: In Defense Of Populism. It will be sent off to the publisher at the end of this month. Writing this book has been an exhilarating experience. Through my research and discussions with policy makers, activists and researchers I learnt much about the contemporary zeitgeist. The bad news is that in the course of examining the hostile reaction to populism I was forces to come to the conclusion that democracy is in big trouble.

Democracy has faced many challenges over the centuries from opponents of popular sovereignty and enemies the demos. In their eyes the people were not fit to influence the political direction of society. Today, hostility to democracy is rarely expressed in an open and explicit form. Instead skepticism bordering on hostility is directed at the capacity of people to play the role of a responsible citizen. From this perspective the majority of society is cast into the role of a 21st century immature mass who lacks moral and intellectual maturity. Worse still the political and cultural establishment assumes that without the guidance of experts people will be drawn towards prejudiced and racist conclusions. Such contemptuous attitudes towards the people indirectly represent a statement about democracy. If the people cannot be trusted, than the moral authority of citizenship is undermined and democracy becomes emptied of its classical meaning.

It would be wrong to react to the ruling classes lack confidence in their citizens by romanticizing the people. As a collectivity, the demos is composed of a variety of individuals, with different abilities and interests. Many of them wish to play an active role in public life and would like their voice to be taken seriously. Others embrace a passive role of indifference to the direction and trajectory of public life. However, what matters are not the peculiar behaviour and attitude of individuals but the invisible cultural bonds that bind people together and provides everyone with a sensibility that is often referred to as common sense. Common sense works as a social glue that allows members of society to develop an outlook based on their shared experience.

The cultural and academic elites frequently dismiss common sense as an expression of an outlook that is clearly inferior to their rational, reason based scientific opinion. Common sense is often ridiculed as merely people’s prejudice. Populism is often attacked on the ground that its cultivation of common sense contradicts the unassailable views of experts. What this contemptuous attitude towards common sense fails to appreciate is that what is important about common sense is the element of commonality! In this vein the German philosopher Hannha Arendt argued that common sense is the lifeblood of democracy. It is through the discussions influenced by common sense that the shared foundation for a meaningful public life emerges. What become integral to the sensibility of the common are the kind of discussions that make democracy come alive.

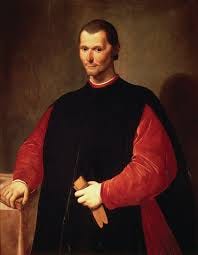

Machiavellii

It was the Renaissance political philosopher Nicó Machiavelli who first drew attention to the value of taking seriously the outlook of the masses. He had an ambiguous attitude towards the masses. At times, his view of the people was one of disdain: he wrote that ‘men are so simple, and governed so absolutely by their present needs, that he who wishes to deceive will never fail in finding willing dupes’. But in his Discourses, Machiavelli adopted a more positive account of the people and claimed that ‘the populace is more prudent, more stable, and of sounder judgement than the prince’[i]. In a chapter titled ‘The Multitude Is Wiser and More Constant Than a Prince’, Machiavelli concluded that when the multitude is governed by laws, it is no less wise than the ruler. He went so far as to see them as the guardians of liberty.

Today it is only movements that are designated as populists who celebrate the wisdom of the masses. One reason why populism is attacked as a danger to the social order is because of its alleged naiveite regarding the common sense of the people. Thus, populists are often attacked for their ‘celebration of ignorance’. For the ruling elites the populist affirmation for the voice of the people as the only genuine form of ‘democratic governance’ represents a veritable scandal[ii].

In recent years the tension between expert and public opinion has assumed a normative character. From the standpoint of the ruling elites expert opinion is not only more scientific than the views of the public it is also morally superior to supposed prejudices of the common people.

In one form or another expressions of contempt towards the demos are shared by almost the entire political class. Leftist often claim that the people are misguided by their false consciousness and have no grasp of their interests. The Green often attack working people for their greedy materialism and their obsession with consumer goods. Liberals regard the demos as composed of immature children whose awareness needs to be raised. From the standpoint of their paternalist orientation important decision making should be left to the experts. Citizens are assigned the modest role of acclaiming the decisions arrived at by their superiors. As for Conservatives, their hierarchical view of the social order prevents them from understanding the vital role that people’s common sense can play in conserving traditional norms and values. Often their mistrust of the masses distances them from enthusiastically affirming democracy.

Democracy is in trouble because the demos enjoys such little moral valuation. And unless citizens are able to play an active role in political life democracy becomes a technocratic medium for maintaining a measure of connection between elites and the people. As matters stand only populism is prepared to democracy seriously and it is for that reason that it has become the target of so much venomous diatribe. In the current moment populism represents our best hope for the flourishing of democracy.

[i] Machiavelli, N., 2009. Discourses on Livy. University of Chicago Press: Chicago, p.116.

[ii] https://harpers.org/archive/2020/05/how-the-anti-populists-stopped-bernie-sanders

American troops in England during WW11 were segregated, but in 1943 publicans in Bamber Bridge put up signs saying 'Black Troops Only' in protest at segregation. Black troops felt so welcome by the white English common people that they felt encouraged to rebel against white American military police trying to enforce colour bars.

The common people were decent in ways that the British establishment was not. Indeed, the working class inter-married in contrast to the middle class which did not. Such was the moral difference that in the sixties there were TV progams such as David Frost's in which the debating topic was 'would you let your daughter marry one'. The chattering class thought so well of themselves sublimely unaware of how behind the times and how morally corrupt they were. Ordinary decent people just got on with life and dislayed a decency that the chatterati did not.

The elites' belief in their moral superiority is self-regarding and a justification for their privileges over hoi polloi. They are the deseriving and the masses, because of their imputed moral failings, are not. The disconnect between governing and governed has led to the Britian becoming close to a failed state where among other disconects we consistenlty vote for lower immigration and degradation of pubic services but get even more of that we have politically asked not to have, in which nothing works and cynicism about politics is at a deservedly all time high.

I'm looking forward to your book!

A very insightful if unsettling piece. We are prone to forget the role of the demos as the source of shared values and understanding. It is also important to remember that the understanding of who made up the Demos was itself politically determined: historically those who constituted ‘the people’ has shifted as a result of the struggle of recognition with the masses winning admission to what was considered ‘the Demos’ on terms set down by the ruling elites. What seems clear is that the values that shaped these terms have changed. What we call the culture war can be taken as the proof that these shared values and view of society have broken down through out the West. The practical political consequence of the culture war is that the sense of a Demos that idea of a shared collectively has been replaced by competing tribes which finds its reductio ad absurdum in the new hierarchy of Intersectionality.